Mali’s sovereignty dilemma

Assimi Goïta’s regime has built its legitimacy on defiance of the West and promises of renewal. But with increasing internal pressure, a turn to Moscow risks deepened dependency.

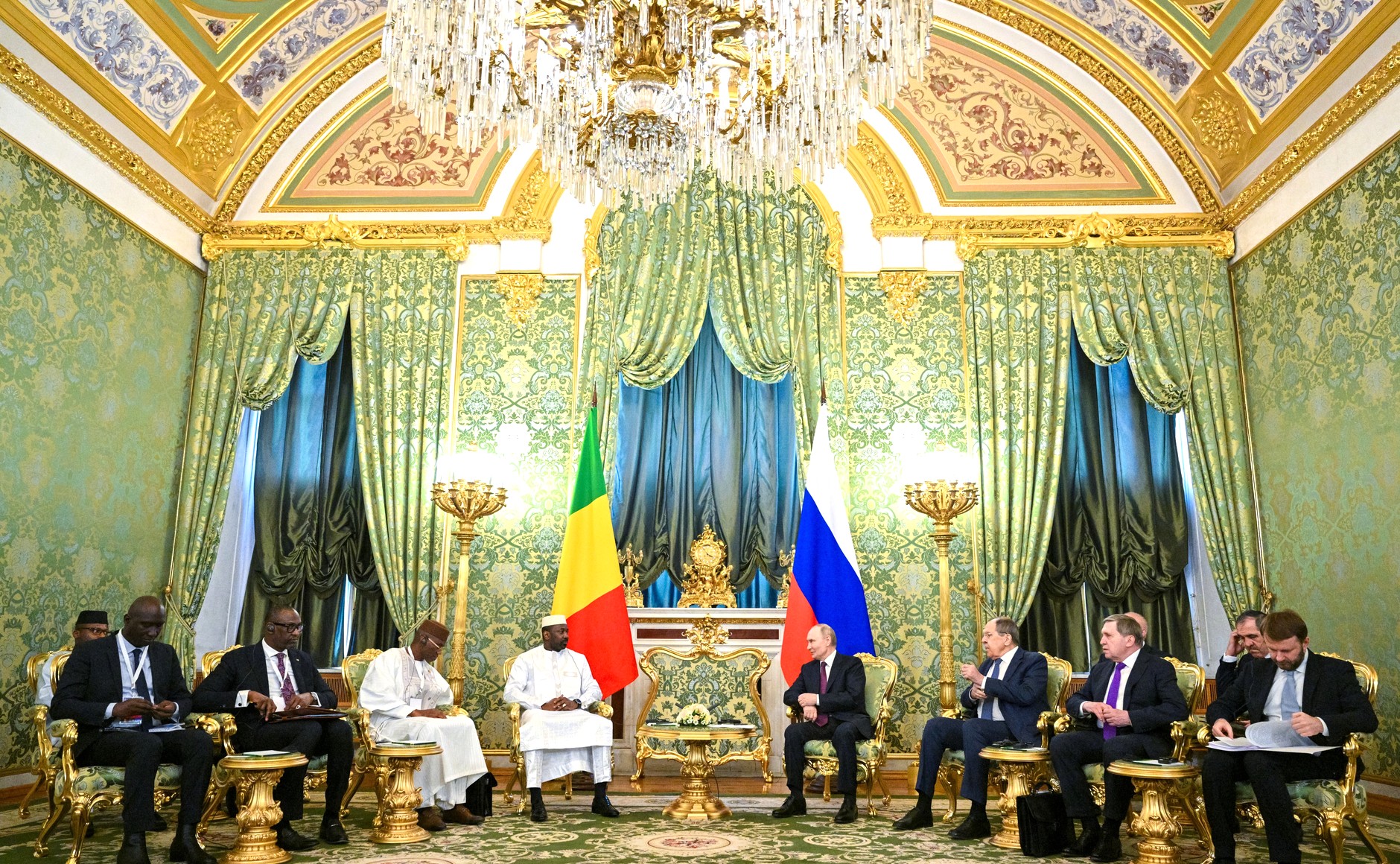

Image credit Ramil Sitdikov, RIA Novosti via The Kremlin.

Since Assimi Goïta’s rise to power through a coup in 2021, Mali’s trajectory has become increasingly uncertain and unstable. Following two military coups in 2020 and 2021, Goïta’s leadership has been marked by a pronounced nationalist stance. His administration emphasizes sovereignty, national interests, and a restructuring of governance, often claiming to prioritize domestic stability and asserting independence from external influences.

While presenting himself as a staunch defender of Mali’s sovereignty, Goïta has actively and strategically realigned his country’s foreign relations. This shift has involved moving away from traditional allies such as France towards closer ties with Russia. This strategic pivot has included accepting security support from the paramilitary Africa Corps, which replaced the Wagner Group, after it withdrew from Mali in June 2025. As a consequence, Mali compelled France to withdraw its Barkhane forces in February 2022. The regime further intensified its independence by expelling the United Nations Multidimensional Integrated Stabilization Mission in Mali (MINUSMA) and terminating the 2015 Algiers Accord.

To bolster internal support, Goïta promised to combat corruption and overhaul Mali’s institutions. His populist rhetoric resonated with many Malians exhausted by elite impunity and governance failures. While these promises initially rallied disillusioned citizens, tangible improvements in security and economic development remain elusive.

Since February 2022, the transitional government has repeatedly postponed elections, citing “technical reasons,” and proposed extending the presidential term until 2030. These delays in Mali and the other Sahelian states have heightened fears of democratic backsliding. On May 13, 2025, Goïta’s government further consolidated power by dissolving all political parties, banning their meetings and citing “public order” as justification. Earlier that month, opposition parties and civil society groups expressed concern about the regime’s drifting into authoritarianism and abandoning democratic reforms. The postponement of elections sparked protests in early May, with opposition groups demanding a return to constitutional rule by December 2025. The government’s response was to dissolve all opposition parties, exacerbating tensions. Internationally, Bamako and its neighboring allies, Niger and Burkina Faso, which together form the Alliance of Sahel States, recently issued a joint statement announcing their withdrawal from the International Criminal Court, calling it an instrument of “neo-colonialist repression.”

Despite persistent political rhetoric, Mali’s regime has yet to deliver on basic services—security, justice, and infrastructure—especially in rural and border regions. For most Malians, living conditions continue to be challenging, as economic growth remains primarily concentrated in urban areas. This urban-centric development has resulted in the neglect of rural regions, where access to basic services, infrastructure, and economic opportunities remains limited, exacerbating disparities across the country. The urban-rural income disparity in Mali stands at approximately 5.5 percent, compared to 2.7 percent in India (United Nations Development Program). Mali ranks 188th out of 193 countries on the United Nations Human Development Index, highlighting its persistent development challenges. In 2023, the country was classified within the Low Human Development category, underscoring its significant struggles in areas such as health, education, and income. Meanwhile, corruption continues to undermine progress. Post-coup, the regime acknowledged widespread corruption within various government levels and pledged reform. However, three years later, while poverty persists, a new class of elites— “the nouveaux riches”—has emerged, evidencing growing inequality. Visible symbols include new housing developments and ongoing infrastructure projects. Notably, Colonel Sadio Camara owns two stables and feeds several horses, illustrating the wealth disparity among the ruling elite. Mali’s economy remains under stress: inflation, constrained external financing, food insecurity, climate-induced losses. However, growth is projected to increase (around 5 percent) in 2025, supported by agriculture, lithium extraction, and services.

The unstable security situation in Mali risks worsening and fueling political instability and enabling armed and terrorist groups to expand. Widespread dissatisfaction and economic hardship are likely to push more youths toward militant organizations, not only within Mali but across the broader Sahel and into West and Central Africa. Groups such as Jama’at Nusrat al-Islam wal-Muslimin (JNIM) and ISIS-Sahel are adept at exploiting grievances, framing government failure as a legitimacy issue. They frequently leverage local frustrations to recruit members and seize control of villages, intensifying the country’s instability.

Despite promises to eradicate terrorism, operational security remains fragile. Mali experiences frequent attacks, ambushes, and violent clashes. These terrorist groups are highly adaptable, exploiting technological advances like Starlink satellite internet, which they are already using to enhance communication and coordination. The proliferation of such connectivity tools not only facilitates recruitment but also boosts the operational capabilities of militant organizations. Furthermore, Starlink exacerbates organized crime, which is deeply rooted in the region’s black markets, including widespread smuggling. Paradoxically, illicit networks enable militants’ access to these devices. With portable, easy-to-use communication tools, terrorist groups are more capable than ever of persuading residents in remote areas—where internet access is limited or absent—to join their ranks. These populations, disillusioned with government neglect, are highly susceptible to terrorist propaganda that preys on their unmet needs.

The Wagner Group’s paramilitary forces failed to defeat the extremist groups. Moscow, under pressure from Algeria, compelled Moscow to revise the group’s role in Mali. From its presence in 2021 to its replacement by the Africa Corps, the Russian Wagner Group played a pivotal role in Mali’s security landscape, stepping in as France and UN forces withdrew. Operating as a private military contractor, Wagner provided direct combat support against jihadist insurgents, training for Malian forces, and regime protection for the military junta. Its presence significantly bolstered the government’s capacity in counterinsurgency operations, including the notable recapture of Kidal in 2023. However, Wagner’s intervention was also marred by allegations of serious human rights abuses, including extrajudicial killings, torture, and terror tactics aimed at civilians, as documented by human rights groups and international media. Consequently, in June 2025, Wagner announced its official withdrawal from Mali, marking a symbolic shift rather than a substantive one. It was swiftly replaced by the Africa Corps, a new Russian Ministry of Defense–controlled force composed largely of former Wagner fighters. This transition reflects a broader Kremlin strategy to formalize and expand its military footprint in Africa under direct state control. While Africa Corps claims to focus on training, intelligence, and logistics, rather than frontline combat, human rights organizations continue to report abuses, while Mali’s security situation remains precarious. Also, the shift from Wagner to Africa Corps signals not a retreat but rather a deepening of Russian influence in Mali, now framed within formal bilateral defense agreements and broader economic cooperation, including energy and nuclear deals. Despite the seeming reorientation of Moscow’s policy on Wagner, Algeria, a close partner, reiterated to Russia its opposition to the presence of foreign mercenaries at its borders.

In late June 2025, Mali’s transitional leader General Assimi Goïta traveled to Moscow, where he met with President Putin. Their discussions focused on deepening bilateral cooperation across defense, trade, energy, agriculture, technology, higher education, and culture. A highlight was signing agreements on nuclear energy collaboration and advancing the construction of Mali’s first gold refinery. Russia reiterated its support for Mali’s security stabilization and economic development.

Russia is only one among various external actors in Mali. Ukraine has played an indirect but active role in Mali’s conflict by providing intelligence, drone technology, and training to Tuareg-led rebels fighting the Malian government and Russian Wagner mercenaries. In July 2024, Ukrainian intelligence helped enable a deadly ambush near Tinzaouaten, reportedly killing dozens of Malian and Wagner fighters. Ukraine also trained rebels in drone warfare, providing drones to the rebels, marking a tactical shift in the Sahel. In response, Mali’s junta cut diplomatic ties with Kyiv in August 2024, accusing it of supporting terrorism—claims Ukraine rejected. The episode illustrates how the Russia–Ukraine war is spilling into Africa, with Ukraine challenging Russian influence but risking diplomatic fallout.

The Arab states in the Gulf region, particularly the United Arab Emirates (UAE), have also been active in Africa, especially in security matters. Despite publicly condemning military coups in Niger, Mali, and Burkina Faso, the UAE has quietly supported some of the new regimes, revealing a gap between its rhetoric and actions. In Mali, the UAE initially opposed the 2020 coup but later funneled funds to coup leader Assimi Goïta. In Niger, it allegedly backed the 2023 coup after former President Bazoum rejected a UAE request to build a military base in northern Niger. The UAE’s strategic aim in the Sahel is to expand its regional influence—especially vis-à-vis rivals like Algeria and Qatar—by securing a northern Niger base to monitor Libya, Chad, and Algeria and support allies like Marshall Haftar in Libya and Sudan’s Rapid Support Forces.

In addition to the UAE and other foreign powers, Türkiye has been actively involved in Mali and the Sahel, involvement which covers a variety of sectors, particularly in defense cooperation. Türkiye’s involvement in the Sahel region has grown significantly over the past years, shaped by its broader Africa policy and its desire to expand geopolitical influence, economic ties, and soft power. Morocco has also become increasingly active in the Sahel, and in Mali in particular, for both military and diplomatic reasons. Rabat positions itself as a mediator and reliable partner, contrasting with Algeria’s formal mediation role. Morocco’s engagement in Mali also reflects competition with Algeria, which traditionally leads Sahel mediation (notably in the 2015 Algiers Accord). By increasing its footprint, Rabat presents itself as an alternative diplomatic and religious partner.

The core issues facing Mali—namely, severe economic underdevelopment, ongoing insecurity, and the expansion of terrorism—remain deeply embedded within its sociopolitical fabric. Neither the Malian Armed Forces nor Goïta’s alliances have succeeded in stabilizing security or improving living standards. Recent oppressive measures, such as silencing opposition parties “to protect national unity,” risk intensifying unrest and regional destabilization. Without decisive reforms focused on governance, economic development, and security, both hard and human, Mali’s future appears bleak. The crisis threatens to spill over into neighboring countries, exacerbating instability across the Sahel and Maghreb regions.

While the presence of the Africa Corps—and external states, for that matter—may help deliver short-term internal stability in Mali, it is far from a cure for the country’s profound and widespread challenges. Lasting stability can only come through a genuine and far-reaching political, social, and economic renewal—one that reflects the needs and aspirations of the Malian people. Rebuilding trust between the population and their leaders is essential, not just for Mali’s future but for the stability of the broader region as well.