Ms. Harris goes to Africa

For all the coverage about Kamala Harris' Afrobeats Spotify playlist, or her search for her grandfather’s house in Lusaka, her African trip is about shoring up US positions.

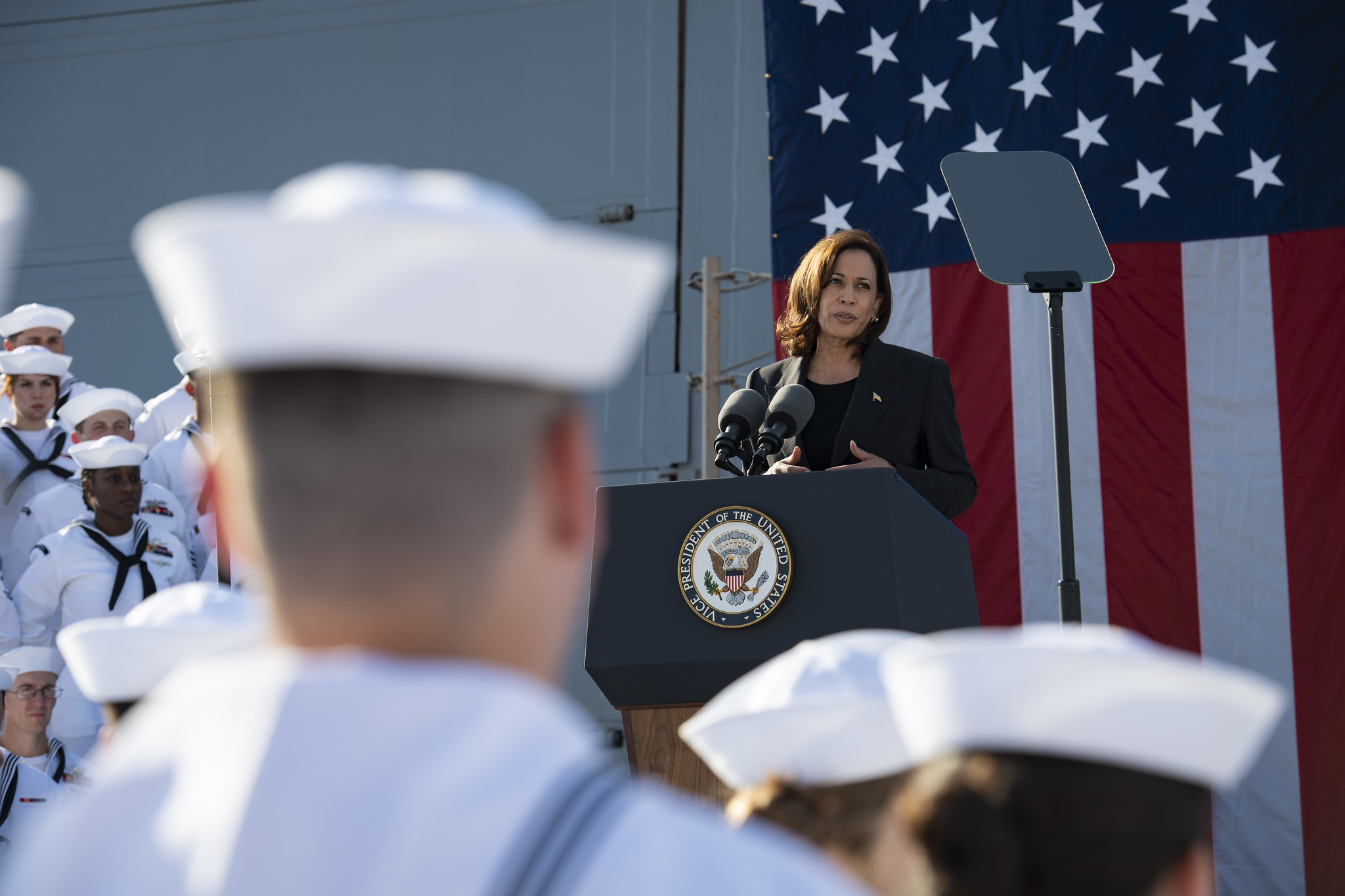

U.S. Navy photo by Mass Communication Specialist 1st Class Kaleb J. Sarten via Flickr CC BY-NC 2.0.

As global political and economic crises pit the US against Russia and China, African people and resources have once more become the target of foreign interest. The new Cold War has brought high-level delegations from all three countries to the continent with promises of trade, aid, and investment in exchange for strategic resources and political loyalty. In the case of the US, Vice President Kamala Harris’s recent trip (Ghana, Tanzania, and Zambia) was preceded by visits from the First Lady (Namibia and Kenya), Secretary of State (Ethiopia and Niger), Secretary of the Treasury (Senegal, Zambia, and South Africa), and UN Ambassador (Ghana, Mozambique, and Kenya). President Joe Biden is expected to call on the continent by the end of the year.

Harris’s mission was to convince her African interlocutors that the US is concerned about Africa for its own sake, not only because of the growing influence of China and Russia in the world’s second most populous, resource-rich continent. She built on the message articulated at the US-Africa Leaders Summit hosted by the Biden administration in December 2022, which emphasized public and private economic investment, the granting of preferential trade agreements, and access to more affordable financing.

Having long prioritized counterterrorism as its main concern on the continent, the US has a lot of catching up to do. China has surpassed it as Africa’s most important trading partner, the former’s $250 billion commerce in 2021 dwarfing US-Africa trade worth $64 billion the same year. The continent is a major source of the minerals needed to produce electric vehicles, laptops, and smartphones, and for the clean energy technologies that combat climate change.

China controls the export of key minerals in the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Zambia, and Tanzania. In exchange for guaranteed access to energy resources, agricultural land, and other strategic materials, China has spent billions of dollars on African infrastructure—developing and rehabilitating roads, railroads, dams, bridges, ports, oil pipelines and refineries, power plants, water systems, and telecommunications networks. Chinese concerns have also constructed hospitals and schools and invested in clothing and food processing industries, agriculture, fisheries, commercial real estate, retail, and tourism.

While the US tends to ignore small countries, engaging instead with powerful regional anchor states, China pays diplomatic attention to small states as well as large ones. It has built loyalties that would take years to challenge. Doing so would require consistent policies developed over many years, continuity through successive presidential administrations, and long-term thinking. As the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq have shown, long-term thinking is not Washington’s strong suit. Mainstream policymakers have trouble thinking beyond the present and specialize in what they hope will be quick military fixes, which have failed miserably.

Russia, meanwhile, has sought new political alliances in response to its increased isolation in the global community. It has supported authoritarian regimes with mercenary fighters in North Africa, Central Africa, the Horn, and the Western Sahel, helping them suppress political opposition in exchange for access to strategic minerals.

In March 2023, Vice President Harris arrived in Africa with promises echoing those made at the US-Africa Leaders Summit. At the 2022 summit, Washington pledged to invest at least $55 billion in Africa over the succeeding three years to strengthen economies, health systems, and technological capacities, combat food insecurity and climate-induced crises, bolster democracy and human rights, and promote peace and security. The Biden White House hoped to distinguish itself from the Trump administration, which had notoriously referred to African nations as “shithole countries” that threatened American well-being with disease, terrorism, and unwanted migrants. The Biden presidency, in contrast, would promote security, democratic governance, and human rights. The development of African military capacities and support for peacekeeping activities would top the list, followed by gender equality, human rights, and the rule of law. Stressing partnership over tutelage, Vice President Harris declared, “…our administration will be guided not by what we can do for Africa, but what we can do with Africa.” Although a Special Presidential Representative for US-Africa Leaders Summit Implementation was appointed, little progress has been made in dispersing the promised funds.

The Biden administration claims to seek a mutually beneficial partnership, but many African leaders remain skeptical. During the first Cold War, a significant number of African states refused to choose between East and West. Instead, they sought allies and investments on both sides and identified as nonaligned. Moscow welcomed the opportunity to encroach on Western turf and established relationships with diverse partners, including liberation movements and states that were avowedly anti-communist. Washington, in contrast, adopted a “with us or against us approach,” viewing those who refused exclusivity as siding with Russia and China. Although the Biden administration professes to feel differently, many Africans are not convinced.

The Biden administration’s record does not bode well for the future. Although the vice president has promised a focus on economic development, the White House continues to privilege military over civilian activities. In this regard, there is little that separates it from its predecessors. Despite the rhetoric, such prioritizing is clearly evident in the president’s budget requests. His FY 2024 request to Congress included $842 billion for the Defense Department—a 3.2 percent increase over the FY 2023 appropriation. This, with an additional $44 billion in defense-related spending for the FBI, Department of Energy, and other agencies, amounts to 47 percent of all discretionary spending.

The administration claims that it will balance security concerns with diplomatic and development activities, yet there is little evidence of this on the ground. Previous Defense Department and security sector budgets in the State Department and US Agency for International Development (USAID) offer proof that African military training has consistently eclipsed civilian-oriented programs. There is little indication that the Biden administration or the present Congress have the will to change this. In a rare display of bipartisan agreement, Democrats have joined Republicans in demanding larger defense budgets. So far, the Biden administration has willingly complied.

Since the establishment of the United States Africa Command (AFRICOM) in 2008, US economic aid has become increasingly militarized. As AFRICOM assumed responsibility for many initiatives previously under the jurisdiction of USAID, soldiers engaged in activities for which they were not trained—and trained experts were shunted aside. Although AFRICOM was billed as promoting “African solutions to African problems,” its programs were developed without significant consultation with African civil societies, and US rather than African security concerns have dominated the agenda.

To enhance the legitimacy and authority of African states, the Vice President Harris has called for improvement in governmental transparency and accountability, anti-corruption measures, and the delivery of basic services. However, she provides little insight into how the US will make these goals a reality—given Washington’s partnership with a number of deeply anti-democratic regimes. Although she promises that these longstanding practices will change, the proof will be in the pudding.

Already, the case of Somalia tells a different story. Since the September 2001 al-Qaeda attacks, the US has been fighting “forever wars” in Africa and Asia. For nearly a decade, US Special Operations Forces have been training Somali troops to combat al-Shabaab, the al-Qaeda affiliate in that country. Despite the infusion of money and manpower, Somali troops have been unable to make significant progress, and al-Shabaab remains strong throughout much of the country’s south. In 2022, the Biden administration reversed Trump’s decision to withdraw US troops and increased the number of US airstrikes by 30 percent over the previous year, taking a heavy toll on civilian lives. In February 2023, Navy SEAL Team 6 targeted and killed a high-level official in Somalia’s Islamic State affiliate, which required President Biden’s personal approval. The Biden White House continues to employ the counterterrorism practices of the past, despite evidence that the targeted killings of Islamic State and al-Qaeda leaders have been ineffective—assassinated leaders are quickly replaced, with relatively little disruption to their networks.

Finally, evidence from elsewhere on the continent indicates that when extremist violence intensifies, lofty goals are cast aside—the US increases military spending and decreases attention to its partners’ corruption, abuses and lack of accountability. The Biden-Harris administration once again is talking the talk, but will it walk the walk this time or double down on the failed policies of the past?