The golden light of Pops Mohamed

From Actonville to global stages, Pops Mohamed blended tradition, futurism, and faith—leaving behind a musical archive as luminous as the spirit he carried.

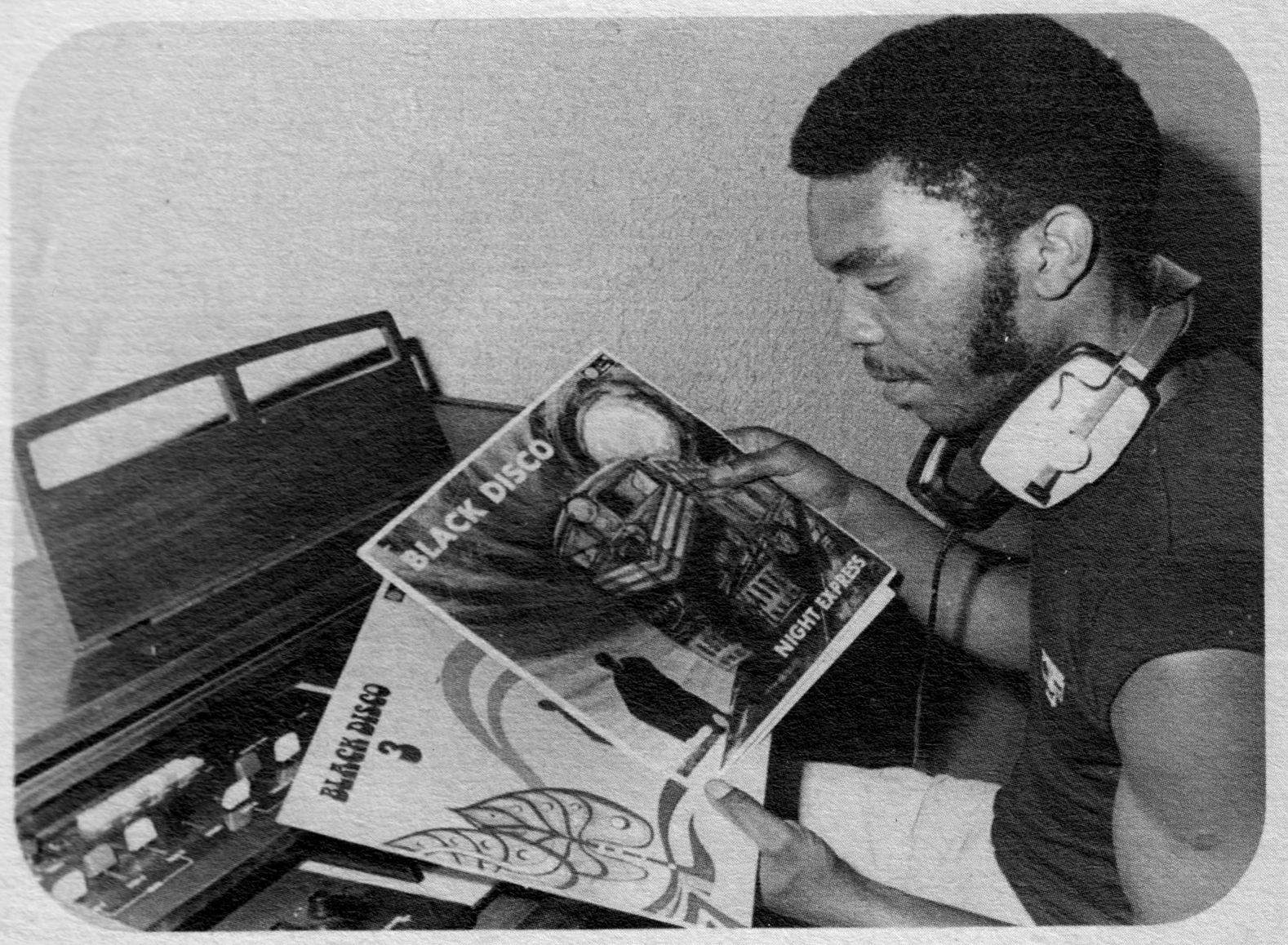

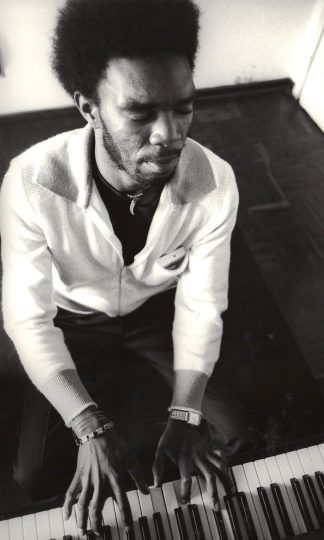

Pops Mohamed looking at the Black Disco records. Image taken from the back cover of the "Black Disco - Night Express" reissue by Matsuli Music. Image © Matsuli Music.

The supermoon shone radiantly on December 4, the night Pops Mohamed died, aged 75. Our neighbourhood in the East Rand of Johannesburg was plunged into darkness due to a power outage, but the sky was lit up brilliantly, as if illuminated solely by the noor (light) of Mohamed’s spirit.

He was a musician, composer, poet, sound healer and producer—a South African cultural hero. Mohamed dedicated 50 years of his life to music, releasing 20 albums and sharing the stage with iconic musicians. He navigated Western, Eastern and African sound worlds with ease, depth, and authenticity. Humility and peace were his defining qualities. He spoke in a very soft, calm and gentle manner. On the morning of his janaazah (funeral), that peace and light filled the air.

He was born Ismail Mohamed-Jan in 1949 in the township of Actonville, Benoni, located east of Johannesburg. In an interview we did just three weeks before his passing, he said:

Music? It just came to me. In primary school here in Benoni, most of the classrooms, at least, had a piano. We used to do music lessons and even in high school. One day, I decided, ‘let me give this thing a go.’ I just played two notes, doom, doom, just moving up and up and thought, ‘this sounds nice!’ Then the next day I would go again and start playing. ‘Oh, I’ve got something here’. Music is something that just came to me.

He attended William Hills High School in the area. “I was in love with the guitar at the age of 14,” he recalled. “I remember our music teacher in high school was Mr. Nakuda, and he used to give flute lessons.” His parents sent him to the iconic Dorkay House, the pulse of arts and culture in central Johannesburg at the time. He would ride the train from Benoni to Johannesburg to attend lessons there. “I didn’t complete high school because I had to leave to work and help the family. My very first job was a spray painter,” he said. “I didn’t stay there for long, I think just over a year, and then I got fired,” he laughed.

When the Group Areas Act reached Benoni in the 1960s, Actonville was segregated as an Indian area, Vosloorus as the Black area and Reiger Park for those of mixed heritage or what the apartheid state termed “Coloured.” Mohamed’s family fell into the latter category because his father was of Indian and Portuguese heritage, and his mother was Xhosa and Khoi. The family was forced to move to Reiger Park in Boksburg.

Describing Dorkay House, Mohamed said:

That was the one place where you could learn to play any instrument. Most of the plays like the Black Mikado and all the plays that went overseas, were workshopped and rehearsed there. Dorkay House had three floors, and the guy who taught us was a German teacher, Mr Gilbert Strauss.

Mohamed stayed there for a year and a half. At the time, popular bands were The Beatles, The Troggs, Cliff Richard, The Shadows and The Flames from Durban. “Playing guitar in those days was a big thing, he recalled, “so you wanted to be a guitar player.”

His first band was called Les Valiants, started when he was 14, and in the years that followed, he earned money on the side playing guitar in several pop bands (The Dynamics, El Gringo’s, Childrens Society) throughout the 1960s. He also took lessons at Federated Union of Black Arts (FUBA), located directly opposite the Market Theatre:

That was another place where you had all the arts under one roof. I went there to study piano. Rashid Lanie was one of my teachers. He was very young then, and then there was a guy called Denzil Weale—those were the guys who groomed me on piano and jazz appreciation. The secretary at FUBA was Sibongile Khumalo. She wasn’t even popular then, but she came from a very talented family, and she helped me with my royal school exams.”

Mohamed got a job at Dorman Long, a steel company in Boksburg, where he worked for 14 years, while doing recordings and gigs over the weekend. It was during this time that he formed a life-long relationship with Rashid Vally—the founder of the iconic jazz record label, As-Shams/The Sun and the popular Kohinoor record store in Johannesburg.

I was still living in Reiger Park at that time. There was a talent scout that heard me playing my organ at home, and he said to me, ‘There’s a guy in Johannesburg. His name is Rashid Vally, and he has a record label. I went with him to Kohinoor, and that’s when I met Rashid for the first time. That was in the early ‘70s. I played him a demo of my music on tape and he loved it. That’s how he arranged for us to record.”

He wanted me to record what he heard on the cassette. I had to take my organ to the studio. He introduced me to Basil Manenberg Coetzee and Sipho Gumede. Both of them are late now, and were such fantastic musicians. We didn’t even rehearse that much, just two or three rehearsals of all the tunes, and we recorded Black Disco.

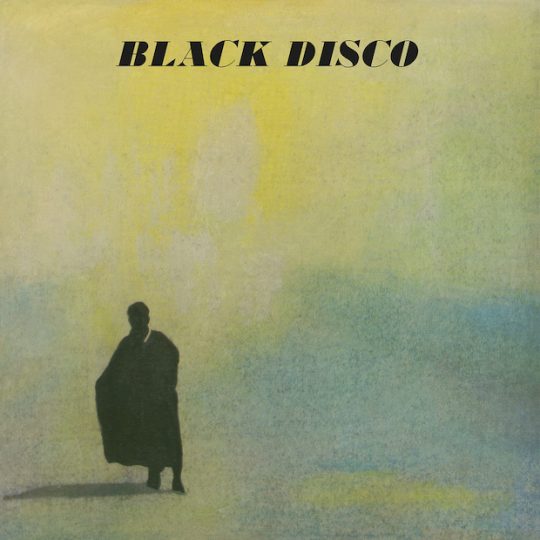

The compositions on Black Disco were a blend of soul, funk and jazz, with Mohamed playing his Yamaha organ, Coetzee on saxophone and Gumede on bass. Their first record was released in 1975.

The trio returned in 1976 joined by Peter Morake on drums for Black Discovery/Night Express (re-issued by Matsuli Music in 2016). The series wrapped up with Black Disco 3, featuring Monty Weber on drums and Peter Odendaal on bass. In Gwen Ansell’s great tribute, she describes how Black Disco was the band’s way of being in solidarity against apartheid. “Black Disco was our way of saying, ‘we are with you,’” said Mohamed.

Following the Black Disco series, Mohamed formed Movement in the City, adding the brilliant Robbie Jansen on flute and drumming by Monty Weber and Gilbert Matthews. They recorded two albums: Movement in the City (1979), Black Teardrops (1981) and the third in the series was just released.

After working in the factory for 14 years, Mohamed decided he’d had enough and wanted to pursue music professionally. He approached Vally to ask if he could work at Kohinoor and learn more about music. “I hated jazz with a passion! The day when I started working for Rashid, he said to me, ‘I’m going to teach you to love jazz as of today onwards.’”

He would play music and tell me the history of the artist, Miles Davis and others. Slowly as customers came in and said, ‘We want this album by Keith Jarrett’ or this album, I would play the tracks that they wanted to listen to. That’s how I started falling in love with jazz and getting to know more about the artists. I would also read the back of the albums, the history and all the write-ups. That’s how I learnt. Rashid was like a mentor in that way. I’ve learnt a lot from him, and we had lots of discussions.” Mohamed continues:

He mentored me to such an extent that he actually would point to an album and cover the name and ask me, ‘Who is this?’ I would guess and say ‘Dexter Gordon,’ or he would play a track on the turntable and ask me, ‘Who’s playing here?’ I would guess and say, ‘Duke Ellington Orchestra.’

Mohamed spoke fondly about his three years working at Kohinoor, remembering that on Fridays, the tiny shop was packed with crowds of people and downtown Johannesburg was buzzing:

It was so busy because on one corner of Kort street, there was a cinema. We had lots of tailors in that street. There was a Chinese shop which sold fish and chips and was quite cheap. Then we had Kapitans as well, which was very popular …the Indian food. Even Madiba went there, and then of course, The Star building was there, where they print the newspapers. Then on the right-hand side, there was a taxi station coming from Soweto. And then we also had the Stock Exchange there as well. That was the hub of downtown Johannesburg. It has a very, very rich history.

We were a happy bunch of people. It was myself, Rashid, his younger brother Chota, and there was a lady who worked with us, Lillian. So Friday is shillaz day. Friday is payday. Everybody’s coming to buy records! And we were always happy. We would buy fish and chips and lots of polony and maybe sometimes biryani, and spend the afternoon eating that food and selling albums, which was really nice.

Vally and Mohamed shared a lifelong friendship and an enduring respect. They also made some brilliant music together. Mohamed described Vally as a friend, brother and mentor, saying “that was an experience of a lifetime, in fact, that is the highlight of my career, because that’s where it all started—at Kohinoor and with Rashid Vally.”

Mohamed was an amazing storyteller. For example, the way he recalls this anecdote about his next big career move:

I was offered to work for a label in England. I met Robert Trunz from Switzerland, who ran Melt2000. He came with Airto Morreira and Flora Purim to Joburg, and they played for the Arts Alive Festival. He also came by Kohinoor, and he had a cassette of mine. I don’t know where he got it. Then he says, ‘I’m looking for Pops Mohammed’. I said, ‘That’s me.’

The pair started talking, and Trunz invited him to the concert at the festival. “I saw them. They were fantastic. And after that, I took him to Kippies to listen to Moses Molelekwa. He was so impressed, like ‘WHAT?’!”

A few days later, Trunz visited the shop and said, ‘How would you like to join my label? I’m starting a record label, but you have to think about it carefully, because I want you to come to England. And then you should recruit all the musicians like Moses Molelekwa and others. I said, ‘Okay, I’ll think about it.’ I thought about it, and then I discussed it with Rashid. And he said, ‘Go for it!’

Mohamed left for England and worked for the iconic Melt2000 label, recruiting and signing the best South African musicians on the label like Molelekwa, Busi Mhlongo, Amapondo, Sipho Gumede and Madala Kunene

Upon returning, he went into his own production because going to studios was very expensive. “I would always check out the engineers. I’m self-taught. I learnt by reading books. I fell in love with sound recording from the very first day that I walked into a studio. I knew this is what I want to do.” Mohamed developed his own sound engineering and production skills, formed his own labels and released his own albums and music videos.

Ansell’s tribute to Mohamed notes how he was inspired by the sounds of Timmy Thomas, but also by the melodies of Kippie Moeketsi. His musical palette was very diverse. Other albums released include the award-winning Ancestral Healing and Kalamazoo, which referred to a small but vibrant multi-racial informal mining township near Reiger Park, which was destroyed by the Apartheid regime. The album has the tune called “Kort Street Bump Jive,” a tribute to the vibrant street Kohinoor was located on. Later, Mohamed released different volumes of Kalamazoo as an album, and also adopted the name for his own label.

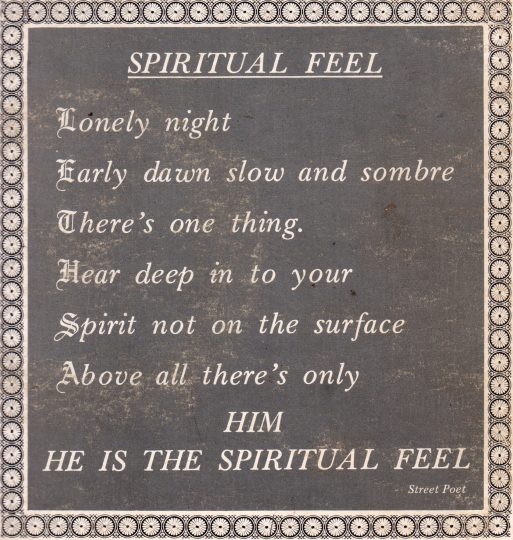

Mohamed was a pan-Africanist, deeply spiritual and nicknamed himself “Futurist.” His work embodied the past, present and future, and he loved experimenting in sound. His music journey drew from ancestral sounds of the Khoi and San in Southern Africa, to West African rhythms and other sounds from the East. He played a variety of instruments, including mbira, uhadi, kora, mouth bow, various percussion, bird whistle, didgeridoo, berimbau, keyboard, organ and guitar. Themes in his music, aside from politics, were often about peace, unity, spirituality and humanity.

Just before the COVID-19 pandemic hit, Mohamed moved back to Actonville to live with his daughter Yasmeen. He got very sick in 2021, but managed to recover and perform again. He received a South African Music Awards Lifetime Achievement Award in 2023.

There was an outpouring of tributes around South Africa at the news of Mohamed’s death. The greatest tributes were from those whose lives he touched. The lawyer and storyteller, Nkazimulo Qaaim Moyeni, wrote on Facebook:

Uncle Pops Mohamed moved through the world with the quiet certainty of a man who had long learned to listen. He spoke about the way he held his spirituality in one hand and his music in the other, and how the two refused to be separated. The drum, the kora, the uhadi and the umrhube were not merely instruments to him; they were gifts. They were tools that opened doors to frequencies older than memory and alive with the essence of Tasawwuf. He told me about how he had written dhikrs carried by the breath of the Uhadi and the hum of the Umrhube. In that moment, I understood that to him, his music was not just sound. It was a way of connecting with Allah; it was a remembrance. It was a way of reaching toward the unseen.

A tribute from friend Ayhan Cetin:

True service is not loud; it is lived quietly, consistently, and sincerely. Pops embodied that. He lived with a heart anchored in humility, loved people without conditions, and used his gifts not for himself but for the upliftment of others. Such people are the unseen pillars of society—those whose goodness holds the world together. And today, the world has lost one of its good human beings, at a time when we need people like him the most.

Finally, his music teacher Rashid Lanie wrote:

My most personal memory of Pops’ brilliance was his relentless curiosity. He was a rising star artist who sought me out with a humble and fierce determination. He implored me to teach him piano, to deepen his understanding of its theory, its discipline of practice, and the intricate language of jazz improvisation. I was endlessly impressed by his scholar’s heart, his willingness to be a beginner again to feed his spirit. But the true surprise, the Pops magic, was witnessing how quickly he parlayed that newfound knowledge into creation. It was with that expanded harmonic vision that he walked into the studio to record with the legendary Rashid Vally of Sun Records, a seminal moment that married his soul with the heart of South Africa’s progressive jazz heritage. That was Pops: a sponge and a spring, absorbing only to pour forth something new and vital … a vision extended far beyond conventional scales and stages. He was, at his core, an Ancestral Poet.

Mohamed has left us not only with life lessons but with many musical treasures, enough to dig into for years to come. At our interview, he was very excited about remastering Kalamazoo Vol. 5 (a dedication to Sipho Gumede), which he released digitally a few days before he passed. On the day he passed, As-Shams Archive shared an archival first digital release of Movement in the City 3.

Mohamed was deeply passionate about Islam, practising the daily five prayers. His connection to Islam was not through words but by actions. On the day of our interview, he reminded me to be silent and listen and be mindful during the Muezzin delivering the Athaan (call to prayer) from our local mosque – something that showed the respect he carried for his faith. Mohamed’s own mixed heritage, his love for Islam, desire for peace, and constant search for knowledge made him the kind of person who could move fluidly through the world. His gentle nature emphasised the lightness of spirit that he carried.

During the last few years of Mohamed’s life, the most important things to him were his faith and his family. He remained a dutiful father and grandfather up to the very end.