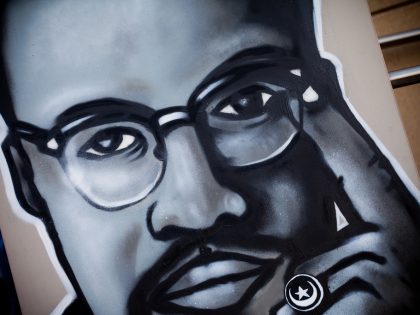

Eric Garner in Palestine

Activists in the occupied territories reinvent the Freedom Rides of 1960s America and in the process link US and Palestinian struggles for liberation.

Image courtesy the author.

Some of the most powerful Palestinian appeals to Black radicalism have come in the form of buses. In November 2011, for instance, six Palestinians in the West Bank disrupted the governing logic of apartheid by simply boarding a bus. Imitating the historic Freedom Rides that took place across the US. South some fifty years earlier, these six Palestinians carried signs and wore T-shirts emblazoned with words such as “dignity,” “freedom,” and “justice.” Included in this group of Freedom Riders was a West Bank professor who writes and teaches about nonviolent resistance and a Palestinian activist who had previously studied at Stanford University with the playwright and Civil Rights Movement historian Clayborne Carson.

The Jerusalem-bound bus these Palestinian activists boarded was filled mostly with Jewish settlers, people who live in Israel’s illegally constructed colonies in the West Bank. When the bus arrived at a checkpoint, several Israeli officers entered it and demanded to see the Palestinians’ identity cards and permits. One of the Freedom Riders, Nadim Sharabati, asked a question of his own: “Do you demand permits from settlers who come to our area?” When one of the officers explained that he was simply following the law, Sharabati replied, matter-of-factly, “Those are racist laws.” When they refused to get off the bus, all six of the Freedom Riders were physically dragged from it, handcuffed, and arrested. Some of the settler onlookers called them “terrorists,” and one of them even told a reporter, “This is not a Martin Luther King bus.”

Media were a central component of the Freedom Riders’ strategy. Speaking to a journalist, one of the activists—a pharmacist named Bassel al-A’raj, who was later killed by Israeli forces during a raid in March 2017—explained that the primary difference between this action and other acts of resistance was, in fact, the presence of media. Before the Freedom Riders boarded the bus, they notified several journalists about their intent, and after their arrest, they released a statement to the press comparing their action to the original Freedom Rides. It read, in part, “Although the tactics and methodologies differ, both white supremacists and the Israeli occupiers commit the same crime: they strip a people of freedom, justice and dignity.” A number of journalists boarded the bus with them, and news of the event was picked up by a variety of established media outlets. The Brazilian-Lebanese cartoonist Carlos Latuff also helped memorialize the event by drawing a cartoon of Rosa Parks sitting on a bus dressed as a Palestinian.

While the 2011 Freedom Ride was just a single occurrence, however, other activists in Palestine have turned it into a regular affair. Since 2012, members of the Jenin Freedom Theatre have organized an annual Freedom Bus that brings together international and local artists, academics, and activists for a one- to two-week trip through the West Bank. Sticking mostly to rural communities and villages, the Freedom Bus aims not only to connect internationals to locals but also to put members of different Palestinian communities in contact with one another, rural and urban, refugee and nonrefugee, diasporic and nondiasporic. Taking its name from the original Freedom Rides that crisscrossed the Jim Crow South, the Freedom Bus is not just a tour; it is a radical cultural event, and artists, bloggers, filmmakers, musicians (including Palestinian rap group DAM), photojournalists, and performers frequently participate. Those on the Freedom Bus take part in political demonstrations in places such as Bil‘in and Nabi Saleh, where there are ongoing popular mobilization campaigns against settlements and land theft; they perform acts of community service, such as the planting of trees in the Jordan Valley and the escorting of Palestinian shepherds in the fields near at-Tuwani, where they are daily threatened by violent Jewish settlers; and they attend media and cultural events, including film screenings, musical concerts, and theatrical performances.

It is worth pointing out that several people involved with both the Jenin Freedom Theatre and the annual Freedom Bus are also intimately linked to Black radical movements in the United States. Constancia “Dinky” Romilly—the onetime partner of the late SNCC leader James Forman—is the president of the New York–based Friends of the Jenin Freedom Theatre. Also on its board is Dorothy Zellner, another 1960s veteran who helped Stokely Carmichael draw the original panther logo later adopted by the Black Panther Party; she more recently embarked on a university speaking tour called “From Mississippi to Jerusalem” in which she discussed the connections between the Civil Rights Movement and Palestine. The Freedom Bus itself has a large list of endorsers, including Angela Davis, Desmond Tutu, Alice Walker, and, before her death in 2014, Maya Angelou, and organizational supporters of the Freedom Bus include the Bronx-based Peace Poets and the Highlander Research and Education Center, the late Myles Horton’s folk school in rural Tennessee that once served as a training ground for such Civil Rights icons as Richard Abernathy, James Bevel, Septima Poinsette Clark, Martin Luther King Jr., John Lewis, and Rosa Parks.

In March 2014, I had the privilege of joining the Freedom Bus. While the connections between it and the Black Freedom Movement were not always explicit, they lurked beneath the surface and occasionally emerged into plain view. In the village of Nabi Saleh, for instance, we met with the longtime peace and justice activists Bassem and Nariman Tamimi. Bassem has been arrested more than a dozen times and spent more than three years in jail for his involvement in organizing protests against the Israeli theft of Palestinian land. He spoke to us about his advocacy of nonviolence and the inspiration provided by other global struggles, including the Civil Rights Movement. We joined him for one of Nabi Saleh’s regular, weekly demonstrations against the gradual takeover of the village’s lands and water spring by the Jewish settlers of Halamish. Armed with only our voices, we were nevertheless met with tear gas. Children from the village, including Bassem’s daughter Ahed, often run to the front lines of these demonstrations, and while some people have criticized their participation at these potentially dangerous events, Bassem disagrees. Speaking to us afterward, he specifically pointed to the example of the Children’s Crusade in Birmingham, Alabama, of 1963, in which Black children were met with Bull Connor’s water cannons and police dogs.

Bassem’s daughter Ahed was quite young at the time of my visit in 2015, but she has since become something of a Palestinian icon. Just a few months after my trip to Nabi Saleh, her image went viral when she was photographed biting the hand of an Israeli soldier in an effort to rescue a boy that he was violently detaining. Even more significantly, in late 2017 a video of her slapping an Israeli soldier was widely distributed via social media, leading to her arrest on assault charges. For the next eight months, she remained behind bars. Remarkably, the discourse surrounding Ahed quickly became a debate about race. Some in Israel had long viewed the Tamimis with suspicion, and it was revealed that the Knesset had once even instigated a classified investigation to determine whether they were a real family or a group of Palestinian actors. According to this conspiracy theory, the Tamimis were all just playing parts, and Ahed was selected for her role because her fair skin and blond hair would elicit Western sympathy. Apparently for her Israeli critics, Ahed was simply too white.

While Knesset members were forming secret committees to solve the mystery of Ahed’s whiteness, others were instead linking her to the Black struggle. In early 2017, Ahed was invited to take part in a US speaking tour alongside Amanda Weatherspoon, a Black feminist liberation theologian. Ahed was forced to forgo the trip after the US Consulate put her visa application under a prolonged “administrative review.” Moreover, shortly after Ahed was arrested, a Black journalist from Philadelphia used the occasion of Martin Luther King’s birthday to author an editorial for Al Jazeera in which he compared her to Rosa Parks, and the US-based Civil Rights organization Dream Defenders released a statement likening her to Trayvon Martin, the seventeen-year-old Black martyr from Florida: “From Trayvon Martin to Mohammed Abu Khdeir and Khalif Browder to Ahed Tamimi—racism, state violence and mass incarceration have robbed our people of their childhoods and their futures.” The statement was signed by many Black artists, academics, and activists, including Michael Bennett, Angela Davis, Danny Glover, Jasiri X, Robin D. G. Kelley, Alice Walker, and Cornel West.

But to return to the Freedom Bus trip of 2015, one of the strongest manifestations of Black radicalism I witnessed took place in al-Hadidiya, a small village in the Jordan Valley that sits just a few hundred yards from the fortified Jewish settlement of Ro’i. We gathered together under a makeshift tent with the longtime activist Abu Saqr and other village residents for a performance of improvisational “Playback Theater” in which the Palestinian actors listened to stories from the audience and interpreted them on the spot. Most of that day’s performances involved incidents of Israeli oppression—namely, confrontations with the Israel Defense Forces (IDF) and Jewish settlers. Toward the end of the performance, however, one of the Freedom Bus riders, a young African American woman, related the story of Eric Garner, the unarmed, Black New Yorker who broke up a fight in the summer of 2014, only to be approached by five police officers and tackled to the ground. As he collapsed underneath the force of a chokehold, Garner repeated the words “I can’t breathe” eleven times before losing consciousness and dying. The entire event was recorded on video and widely shared on social media, but a grand jury refused to indict any of the officers who murdered him. There, in a tent in al-Hadidiya, amidst squawking chickens and bleating sheep, the Palestinian actor Motaz Malhees reenacted this saga, contorting his face to emulate Garner’s final fatal moments. Most of the Palestinians in the audience had not heard the story of Garner, and seeing this tale of racist US aggression reinterpreted in the context of Zionist settler-colonialism was powerful and moving. It was a moment in which the idea of tying together the oppressed communities of both countries became tangible, a moment in which transnational Black solidarity became more than mere specter.