Egypt and the Afrocentrists: The latest round

Why did North Africans and Middle Easterners almost overnight go from being comrades-in-struggle to racial intruders in Africa and in African American cities?

Giza. Image credit Catherine Poh Huay Tan via Flickr CC BY 2.0.

Like relics from a bygone era, these figures with their colorful outfits and flamboyant theories still surface on university campuses, community centers, and social media. In Harlem, there is Leonard Jeffries, who taught Black Studies at the City University of New York before he was discharged for his rhetoric about “ice people,” “sun people,” and more recently “sand people.” Down the road at Columbia University, one can find Abdul Nanji, a piteous character, a tutor of Swahili language, who also spouts theories of Asian invasions of Africa. Further south in Philadelphia, Molefi Asante at Temple University holds forth on how the Islamic invasion of Africa destabilized the entire continent, though his more recent thesis is that it was a combination of Marxism and Islam that derailed “The Black Movement.” Asante made headlines in the early 1990s with his claims that Cleopatra was black (and not Greek Macedonian), and that the Greeks stole Egypt’s heritage. This argument would prompt Wellesley classics professor, Mary Lefkowitz, to publish her polemic Not Out of Africa: How Afrocentrism Became an Excuse to Teach Myth (1996), which would trigger more mudslinging and multiple lawsuits.

These were the culture wars of the early 1990s, as distant as Operation Desert Storm, or Public Enemy topping the charts. Today’s American youth are not particularly invested in North African antiquity or Cleopatra’s skin color. And yet a few weeks ago, Afrocentrism was trending, as were names and rhetoric last heard three decades ago. It was déjà vu all over again, except now it was on Twitter with lots of DNA-talk.

The hashtag #stopafrocentricconference took off in late January. Amr el-Kady, a young Egyptian activist posted a thread, warning that “something dangerous” was going to happen in Aswan: a so-called “Afrocentrist University” was going to hold a conference in Upper Egypt, and the choice of Aswan was deliberate, because this movement exploits ethnic and cultural difference, and aims to “polarize” and separate Nubian youth from Egyptian society. El-Kady cautioned that the Afrocentric movement would use “counterfeit” history to destabilize the country, tear up its national fabric and create fitna (strife). He attached an ad for the “One Africa: Returning to the Source Conference” sponsored by the New York-based Akhet Tours and Hapi, to be held in Aswan in late February, in honor of Black History Month. The conference promised to bring together “some of the world’s eminent scholars of African history” who would “unpack the historical connectivity and confluence of African people as they migrated throughout the continent.” Soon Egyptian Twitter lit up with clips of Afrocentrists giving tours of the Pyramids and talking about Kemet (when Egypt was a “black land”). A quote by Egyptologist Solange Ashby went viral, “What about the usurpation of African history in Egypt by the Arabs who only arrived in 642 CE?” A young woman working for the Ministry of Tourism put out a video decrying the Afrocentrists’ attempts to steal “our” history. Another activist said Egyptians should join forces with the Amazigh people, Native Americans, and Polynesians who were also having their history appropriated by Afrocentrists.

Then a clip began circulating of Zahi Hawas, the controversial former Egyptian Minister of Antiquities, talking about how Afrocentrists had protested his lecture at a museum in Philadelphia because he refused to perform DNA tests on mummies, and questioned the right of Black Americans (who are largely of West and Central African descent) to lay claim to civilizations in northeast Africa or the Nile Valley. Hawas has in the past referred to Afrocentrists, (and their more recent iterations, Hoteps, Kemetists, and Foundationalists) as “Pyramidiots.” Ironically, when US president Barack Obama visited Egypt in June 2009, Hawass was tasked with giving him a tour of the pyramids. Memorably, inside the Tomb of Qar, Obama would spot the hieroglyph of a pharaoh and exclaim, “That looks like me! Look at those ears!” Soon thereafter a conspiracy theory emerged claiming that Obama was a reincarnation of the pharaoh Akhenaton, (though as the Libyan and Syrian civil wars dragged on, Islamists responded that Obama was the Dajjal (the Deceitful Messiah), rather than a cloned pharaoh. Hawass the Egyptologist has since argued that the Egyptian president Abdel Fattah Al-Sisi is Mentuhotep II.

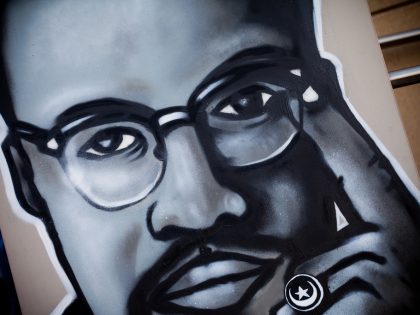

By mid-February, the One Africa conference was canceled. More racial vitriol ensued as Egyptian activists claimed victory, and American observers saw the entire brouhaha as evidence of an abiding Arab racism. At the heart of this imbroglio is a sense on both sides of the Atlantic of dashed expectations and solidarity betrayed, that the sacrifices and comradeship of past decades had not been reciprocated. Grand expectations were forged in the early 1960s when a number of African American intellectuals, such as Malcolm X, Shirley Graham DuBois, Julian Mayfield, and Maya Angelou spent time in Cairo. They supported the Nasserist revolution, and saw themselves and Egypt, as part of a rising Africa and third world. W. E. B. Du Bois would famously write a poem: “Beware, white world, that great black hand which Nasser’s power waves.” Malcolm X would declare “my heart is in Cairo,” and describe how an encounter with a “white” Algerian revolutionary led him to redefine his understanding of Africa and black nationalism.

By the early 1970s, however, this Islam-friendly black nationalism was being challenged by an Afrocentrist movement that was staunchly anti-Arab and anti-Muslim. Islam, according to this narrative, had done as much damage, if not more to Africa, as Christianity had, and the Arabs were “white invaders” on African soil, akin to European settlers, who conquered the New World. In 1971 Chancellor Williams published The Destruction of African Civilization, which would emerge as one of the founding texts of the Afrocentrist movement. Williams described how since the time of pharaonic Egypt, Arabs had attempted to conquer Africa while Nubians and Ethiopians heroically resisted the white “Arab-Asian” effort to destroy the single black kingdom that originally extended from the shores of the Mediterranean to the source of the Nile. Molefi Asante would write, “The Arabs, with their jihads, or holy wars, were thorough in their destruction of much of the ancient [Egyptian] culture,” but fleeing Egyptian priests dispersed across the continent spreading Egyptian knowledge.

Scholars have exhaustively refuted these claims showing North Africans have always been multi-hued, and there is no evidence of a black North Africa obliterated by invaders. One prominent geographer writes, “It was not that Arabs physically displaced Egyptians. Instead, the Egyptians were transformed by relatively small numbers of immigrants bringing in new ideas, which, when disseminated, created a wider ethnic identity.” Another historian argues that both skeletal and ancient pictorial evidence “show ancient Nubians as an African people fundamentally the same as modern ones” and that the advent of the Arabs “has had a powerful linguistic, religious and cultural impact but has … not had a great influence on the appearance of the people.” Even Cheikh Anta Diop, the great Senegalese thinker, has called the belief that Arab invasions caused mass racial displacement into sub-Saharan Africa a “figment of the imagination.”

Multiple scholars have covered these debates. More interesting for our purposes is why did Middle Easterners, almost overnight, go from being comrades-in-struggle to racial intruders in both Africa and American cities? Observers have noted that the decades-old Sudanese civil war drew African-American attention to anti-black racism in the Nile Valley. But the Sudanese conflict began in 1983—after the emergence of Afrocentrism—and the Afrocentrists have expressed little interest in state policy, or joining local coalitions to defend Nubian rights or counter anti-black racism. Others have noted that the increase of Middle Eastern grocers in American cities after the Immigration and Naturalization Act of 1965 created resentment, but Middle Eastern merchants have been peddling their wares in American cities since the 1930s (as the history of the Nation of Islam and W.D Fard attests.) Why did these immigrant grocers come to be seen as blood-sucking exploiters only in the early 1980s?

The shift in African-American opinion seems more likely linked to broader geopolitical shifts following the 1967 War. Starting in the mid-1950s, Egypt was clearly supporting the African-American struggle, offering scholarships to students in the segregated South, and providing diplomatic support in international institutions such as the Organization of African Unity and the United Nations. Similarly, Algeria offered diplomatic support and gave refuge to the Black Panthers. Through the 1960s, Cairo and Algiers supported liberation movements across the African continent. In the early 1970s, both Algeria and Egypt abandoned this position of support for black radical protest, as they joined the American camp in the Cold War (with Algeria expelling the Panthers in 1973 in exchange for a $1 billion natural gas agreement with the US). Ironically, in Egypt, the turn away from Africa happened under the leadership of Anwar Sadat, the Nubian president, who told American journalist Barbara Walters that he was tired of how the Soviet Union was treating Egypt like “a central African country.”

Equally important to understanding this shift in opinion is the role of domestic lobbies in the US—in particular evangelical and Zionist groups, aided by a loose coalition of liberal and conservative activists, writers and state officials, who sought to separate the Black freedom movement from Africa, the Arab world, and the third world more broadly.

Morocco has faced a movement similar to the Afrocentrists in the Moorish Science Temple, whose members claim to be the original Moroccans—yet Rabat has since the 1980s invited members of the group to Morocco for tours and conferences. Granted, in the US there are no interest groups invested in Moroccan history, as there are with Egypt.

These debates died down in recent decades. Black Lives Matter is more focused on domestic state violence and structural racism than foreign affairs. With the expansion of African migration to the US, the conversation about Africa has tended to be driven by the children of African immigrants and focused on specific countries rather than mythological attachments to the Nile Valley. Yet, these old culture wars still occasionally flare up, going global as happened last month. Progressive voices seem to have given way to parochial nativists on both sides. One thing this recent kerfuffle has also revealed is that the image of the African American has taken a battering in recent decades, with Muslims keenly aware of how both Condi Rice and Herman Cain, may evoke civil rights and Birmingham, but call for perniciously anti-Muslim policies.

The solution, however, is not to cancel the One Africa Conference, or the Afrocentrists, but to understand the origins of this Afrocentrist movement and to engage in respectful dialogue. Afrocentrism must be understood as a response to a centuries-old, colonial Hegelian policy of dividing Africa into three parts: “European Africa” that lies north of the Sahara; Egypt, the land connected to Asia; and “Africa proper,” the land below the Sahara, which the German philosopher Hegel called “the land of childhood, which lying beyond the day of self-conscious history, is enveloped in the dark mantle of Night.” During the colonial era, this partition of Africa would be compounded by the “Hamitic thesis,” which held that anything worthwhile in “interior Africa,” any sign of civilization must have come from the Semites, Middle Eastern, or Berber, or European influence. (Thus when Hawass says “the Ancient Egyptian civilization did not occur in Africa” he may be using “Africa” as a byword for “sub-Saharan Africa,” a common enough short-hand as far south as Ethiopia, but his language and claims that ancient Egyptians were “pure Egyptians” evokes the anti-black, white supremacist language of Hegel).

Starting in the mid-19th century a number of African-American thinkers, such as Martin Delaney, would try to counter this white supremacist narrative, with what historian Wilson Jeremiah Moses has termed a “vindicationist” black nationalist historiography. Pharaonic Egypt would figure prominently in this black nationalist discourse. In fact, 19th century Egyptomania across the US was related to anxiety about race and slavery. W.E.B Du Bois’ The World in Africa, published in 1947, would offer a powerful counter to this Eurocentric mapping of Africa, by showing how Egypt and the Moorish empire were part of the continent’s history and composition.

Recent iterations of Afrocentrism have tended to focus on DNA, calling for DNA tests on mummies to show, once and for all, that the ancient Egyptians were black, and different from the country’s current inhabitants. This latter argument has long existed and been dismissed in Egypt. The recent controversy made headlines in part because currently Egypt, like other African states, is trying to have pharaonic artifacts returned from Western museums, and the Sisi regime has sought to manipulate the pharaonic past. As one Cairo-based Egyptologist wrote, in explaining her discomfort with the One Africa conference:

The alienation of modern Egyptians from their ancient heritage and posing them as “Arab invaders” (and occasionally a mix of Greeks and Persians in the case of Copts) is used as justification to deny Egyptians’ claims over a significant part of their cultural heritage. I have heard outright Egyptologists and museum curators in the West, in personal correspondences, panel discussions, conferences and on social media shut down discussion of repatriation of artifacts using these bogus claims about the “racial differences” between ancient and modern Egyptians or because Egyptians are Arab invaders … Some of this is good old Eurocentrism but a very significant portion of it is Afrocentrism.

This is all happening while Al-Sisi, like earlier Egyptian strongmen, is tapping the Pharaonic past to shore up popular support, and claiming a direct continuity between pharaonic Egypt and the modern Egypt state. The very regime that crushed sundry opposition movements placed a 90-ton Ramses II obelisk in Tahrir Square. In April 2021, the regime took 22 mummies from the Museum of Antiquities, and staged a nationally-televised procession called the “Pharaohs Golden Parade.” Sissi praised the parade: “This majestic scene is evidence of the greatness of the Egyptian people; the guardians of this unique civilization extending deep into the depths of history.” Historian Khaled Fahmy would, in a tweet, lament this “racialization of history” and its disturbing resemblance to mid-century European fascism’s mobilization of ancient history.

Egyptians are understandably wary of irredentist Western movements that try to redraw local histories and borders along racial lines (given US policy in Iraq and Sudan), and that call to reclaim or resettle their country, given the history of Palestine next door (and African-American settlement in Liberia). But dialogue with Afrocentrism can still be fruitful, if only to understand the struggles that forged this perspective. Leonard Jeffries of City College studied in Lausanne, Switzerland in the 1950s, before going on to receive a doctorate in political science from Columbia University under the direction of Immanuel Wallerstein, who became a founder of the influential Dar Salam School with Guyanese historian Walter Rodney and Egyptian scholar Samir Amin (the latter had left Cairo for the Tanzanian capital following Nasser’s death). Why did Jeffries turn away from European social liberalism, or Walter Rodney’s Third Worldist path to liberation, and opt for melanin theory? Likewise, Abdul Nanji sounds sadly unlettered when he rants about Asian and Semitic colonialism in East Africa, until you realize that he came of age as a Tanzanian of Indian descent at a time when Nyerere’s TANU-led regime was adopting indigenization policy and spewing anti-Asian rhetoric. Once he settled in Harlem, he had to pick sides. Likewise, James Small, who was slated to speak at the One Africa Conference, was the imam of Malcolm X’s Muslim Mosque Inc for decades and has spoken movingly of his struggles while living in Saudi Arabia.

One of the more fascinating scholars scheduled to speak at the Aswan conference is the 86-year old Congolese born linguist Théophile Obenga, professor emeritus at San Francisco State University, who worked closely with Cheikh Anta Diop. Both attended UNESCO’s historic 1974 summit on “the peopling of ancient Egypt” in Cairo. Obenga would go on to challenge the colonial mapping of African languages by observing that the similarities between ancient Egyptian (as preserved in Coptic) and various sub-Saharan languages were stronger than the links between Semitic, Berber, and Egyptian languages (the so-called Afro-Asiatic languages). He would go on to propose three major language families for Africa—Berber, Khoisan, and Negro-Egyptian. Obenga and Diop were deeply engaged in the work of decoloniality, trying to undo the epistemic categories and discursive arrangements inherited from colonialism. Countless North African scholars are trying to do the same. Since the uprisings of 2011, and renewed debates around national identity and official historiography in North Africa, there is growing interest in the work of Cheikh Anta Diop and Obenga.

Perhaps a One Africa conference can be held next year in Aswan, and the Afrocentrist elders can be invited to Aswan to meet with younger Egyptian scholars and activists in a conversation free of accusations of settlerism and blood purity. Maybe participants from across the continent can join, and engage in a conversation on the meaning of ancient Egypt, the Kingdom of Kongo, and Great Zimbabwe for pan-Africanism today. It is One Africa after all.