Repoliticizing a generation

Thirty-eight years after Thomas Sankara’s assassination, the struggle for justice and self-determination endures—from stalled archives and unfulfilled verdicts to new calls for pan-African renewal and a 21st-century anti-imperialist front.

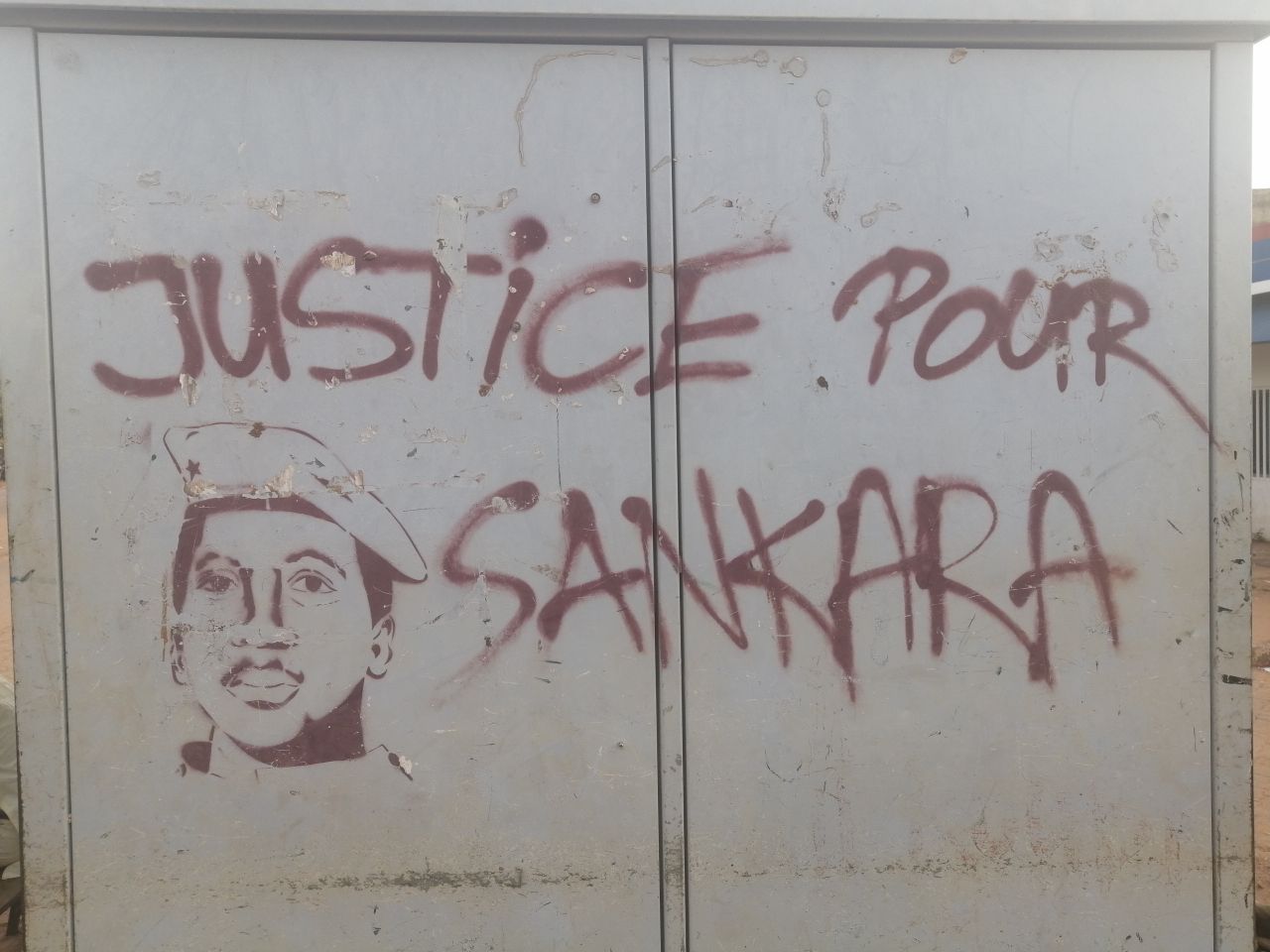

Thomas Sankara graffiti. Image credit E. Kokou via Wikimedia Commons CC BY-SA 4.0

- Interview by

- Amber Murrey

Yesterday marked the 38th anniversary of the assassination of Thomas Sankara, who, on October 15, 1987, was killed alongside twelve of his comrades during a coup led by Blaise Compaoré. Sankara’s brief but transformative presidency (1983–1987) reoriented Burkina Faso’s political economy toward self-reliance, gender equality, ecological stewardship, and non-alignment in global affairs.

For more than three decades, Aziz Salmone Fall, a pan-African activist, political scientist, and coordinator of the International Campaign Justice for Sankara (ICJS), has worked with Sankara’s family, Burkinabè activists, and international allies to demand truth and accountability. The long struggle has yielded historic breakthroughs: Compaoré, his former chief of staff, Gilbert Diendéré, and former Burkinabè army captain, Hyacinthe Kafando, were convicted of complicity in murder by a military court in Ouagadougou in April 2022. Significant questions remain regarding the enforcement of the verdict (each was sentenced to life imprisonment), the release of the French archives, and the larger fight against impunity.

In this conversation between Amber Murrey and Aziz Fall, Fall reflects on the enduring significance of Sankara’s revolutionary ideas and the ongoing movement for justice. They explore how the campaign navigates legal and diplomatic obstacles; how new regional dynamics such as Senegal’s political shift to the creation of the Alliance of Sahel States, shape ongoing political and economic struggles; and how a generation of African youth is being reinvigorated by Sankara’s vision of a sovereign, ecologically attuned, and socially just future.

Aziz envisions a renewed pan-African and anti-imperialist front grounded in what he calls the “Great South:” a collective of emancipatory forces reclaiming political and epistemic agency from the global periphery. Through his concepts of transinternationalism and a revived “Bandung 2” internationalism, he calls for a 21st-century alliance that transcends the nation-state, uniting peoples of the South and North in a shared struggle against imperialism and capitalist domination.

The campaign you coordinate has long demanded justice for the assassination of Thomas Sankara. What were some of the lessons you learned over these three decades of organization?

Thank you, Amber, for this opportunity to reflect at this important historical moment. The first lesson is that when we organize ourselves with self-sacrifice, courage, and audacity, anything is possible. In the summer of 1997, a few months before the [administration’s claimed] 10-year statute of limitations expired, Sankara’s widow, Mariam Serme Sankara, courageously filed a complaint against X for forgery. Our lawyers Dieudonné Nkounkou from Montpellier and Bénéwendé Sankara from Ouaga took up the case and assumed her defense. GRILA launched the ICJS international campaign Justice for Sankara in the form of an appeal against impunity. The appeal was endorsed by several organizations and prominent figures. I had the honor of coordinating this group of some 20 lawyers and, over the course of these decades, exhausting all remedies before the Burkinabè courts, which were manipulated within la Françafrique, and we appealed to the United Nations Human Rights Committee and obtained an international precedent against impunity in 2006.

Relentless campaigns to raise awareness of Sankarism and Pan-Africanism have borne fruit. Young people have taken up the cause. With the overthrow of the Compaoré regime, a new administration has allowed a new trial to be organized. It opened on October 11, 2021, and has resulted in the conviction of those who murdered Sankara and his comrades.

The second lesson is that some consider this to be a Pyrrhic victory. I have a great moral responsibility in this matter and am uncomfortable with its outcome. Most of the families who agreed to allow me to exhume the bodies were disappointed to see that there was insufficient DNA evidence to identify them. It must be said that the previous regime had not protected the Sankara site, where liquids had been poured over his grave in an act of desecration. The state preferred to use laboratories of its own choosing rather than those we had recommended. And when it came to reburying the bodies, the Sankarist supporters were divided between those who (along with the majority of the families) believed that they should not be buried at the Council of Entente where they had been slaughtered, and those who, supported by the current regime, and other Sankarist supporters, believed that a memorial should be erected there: the Sankara Memorial. It was recently inaugurated and is now their final resting place. In order not to embarrass the families, I declined the state’s invitation to the inauguration and the medal that was to be awarded to me. I had proposed a vacant space between the Cuban Embassy and the Council of Entente as a compromise, but this proposal was not accepted.

The third lesson is that despite our struggles, the culture of impunity can persist. The chief orchestrator is still protected by Françafrique, which refuses to die, and the current authorities—who claim to be Sankarists—have yet to request his extradition.

Where do we stand today in terms of accountability and impunity, particularly concerning the conviction in absentia of Blaise Compaoré? What concrete steps will be taken next to ensure that the verdict is enforced?

It may be surprising that a person who has committed so many atrocities, who has murdered his close comrades and many other opponents, whose henchmen have threatened us with death, who enriched himself by plundering the sub-region and who, moreover, contributed to introducing terrorism there, can enjoy, in complete tranquillity, the nationality of Côte d’Ivoire, a country he helped to destabilise, and live there in luxury. We take this opportunity to reiterate our request to Burkina Faso to demand his extradition, to Côte d’Ivoire to respect the deserved sentence he has received, and to France to stop supporting him. Perhaps the current regime in Burkina Faso fears Compaoré’s capacity for harm if he were imprisoned in Ouagadougou, but that is just speculation on our part. For our part, while once again congratulating our courageous lawyers, this part of the trial has been resolved, and we have achieved our objective of ensuring that justice is heard, something that had been denied us for so many years. At the level of international law, following the deaths of human rights experts [Louis] Joinet and [Doudou] Guissé, and despite their courageous efforts, we still do not have a binding convention on impunity.

Access to national and international archives is vital to establishing historical truth. What progress has been made in releasing key documents from France or other countries? What strategies are being used to overcome political and diplomatic obstacles to full declassification? Is your sense that the thin portfolio of archives released by the French during the trial is the end of that process?

We have spent decades requesting the declassification of secret and strategic documents. France has disclosed a batch of strategic documents, but these do not incriminate it. A third batch that was to be provided has been blocked by the French authorities. The rogatory commission that was to work on opening the international aspect of the trial, which was separated by the Burkina authorities, appears to still not have been set up [as of 2025]. There is a clear lack of willingness on both sides to finalize the resolution of this case. Our lawyers have unsuccessfully tried to get the authorities to take action. It is true that the situation of terrorist insecurity in the country and the region does not help matters. My reading of the documents and my assumptions clearly point to international sponsors, mainly French and American, and a few regional second-tier players.

The recent political changes in Senegal have generated hope, including the appointment of Ousmane Sonko as prime minister and the plans to phase out the presence of French military forces. How do you assess the prospects for progressive change under the new government, and what role could Senegal play in supporting justice initiatives, such as the campaign for justice for Sankara?

I have already had the pleasure of seeing the current prime minister give an interview at the beginning of his term, with a large poster of Sankara in the background, and he even attended the recent inauguration of the Sankara memorial. These are strong political signals. However, we did not receive any support or show of solidarity from his party during our campaign. It must be said that one of the characteristics of the AES and Senegalese regimes is that they are distinguished by their declarative and sometimes even active sovereignty, but they do not associate with revolutionaries. This may be a tactic in the face of imperialism, which is indeed powerful against young and fragile regimes. For the moment, we have a polite and distant relationship with all these regimes, which are not unaware of our pan-African sacrifices and struggles, which they themselves claim to support. In the case of Senegal, I proposed the pan-African platform Seen Égal-e Seen Égalité, a progressive, feminist, and ecological self-reliant social project. Seven parties have endorsed it and six candidates have chosen to draw on elements of it for their programs.

The regime has not endorsed it, but there is a certain influence, and it espouses an anti-neocolonial and anti-imperialist rhetoric. In practice, however, there will be no anti-capitalist break, but rather a pragmatic liberal management of the crisis, which we hope will be more patriotic than that of the former regime. But if there is already patriotic management of public funds and the settlement of impunity for financial and bloody crimes, that would already be a lot. We believe in a gradual break and will therefore continue in this vein, as we see no other options for Africa.

Young people across the Sahel and wider Africa are increasingly politically active in digital spaces and online communities. How does the Justice for Sankara Movement inspire and connect with this new generation to build pan-African alternatives to both external domination and authoritarian statecraft, for example, in Cameroon, Chad, and elsewhere?

We are convinced that our struggle against apartheid and for national liberation, followed by three decades of fighting against impunity and promoting Sankarism and Pan-Africanism, have helped to shape thousands of young people and generations of conscious Africans. At the same time, this politicisation is often superficial, as young people globally have been affected by three decades of depoliticisation caused by neoliberalism and the divestment of the state. I believe that those who have accompanied us in this struggle against autocracies, foreign bases, or pan-African development, and who have even supported it, are different from others in their pan-African consciousness. But it is a long and difficult struggle against a hostile world order and stubborn and perverse autocracies that have contributed to perpetuating ignorance, obscurantism, and all kinds of diversions to distract young people from their historical responsibility for transformation. But the contradictions and demands of life and survival are leading these young people to discover our struggles, which are identical to theirs, and the ancestors of the future, from Cabral to Ben Barka, from Lumumba to Fanon, who illuminate our struggles.

The formation of the Alliance of Sahel States (AES) by Burkina Faso, Mali, and Niger marks a shift in Sahel geopolitics and autonomy. From the standpoint of the region’s peoples and movements, what are the most exciting aspects of recent moves?

Undoubtedly, greater collective self-esteem. The simple fact that African countries are uniting in the face of adversity is progress. The fact that these are military juntas does not seem problematic to me; Sankara and his comrades were indeed soldiers with a certain social conscience. The sovereigntist stance and determination to fight the terrorist hydra, even if it means abandoning historical external support and favoring others, cannot be achieved at the expense of democracy or regional and pan-African dynamics. We need an open stance toward all peoples and all their components, and not just the military, which does not have a monopoly on politics. We must be confident and not suspicious. We must stand up against the tide of autocracy on the continent. In Tunisia, my comrade Khayam Turki has been accused of conspiracy and sentenced to two decades in prison with complete impunity; in Benin, my comrade Lehady Soglo is still convicted and in exile on unclear charges; our comrade Gbagbo in Côte d’Ivoire was previously rendered ineligible for major elections [this ineligibility was lifted in 2023]; Maurice Kamto in Cameroon has also been brutally sidelined [in the 12 October 2025 presidential elections]… Libya, Congo, and Sudan are being carved up and preyed upon by profiteers, bandits, extractive industries, and more. These circumstances do not allow for the clarity and serenity needed to build Pan-Africanism. For example, the AES is falling out with Algeria and paradoxically turning to Morocco. What about the Sahara issue, or other West African trade routes? Our leaders must learn to disconnect to ensure better accumulation, consult each other more strategically, let our peoples flourish, and not adorn themselves with medals, honours and enrichment; and concern themselves with questioning the old model of development by opting for a balance in symbiosis with nature that satisfies the essential needs of those who are deprived, proposing strategies for full employment, redressing inequalities, particularly concerning the status of women, and educating for progressive knowledge… these are some of the signs we are waiting for in concrete terms.

As you know, this month marks the 38th anniversary of the assassination of Sankara. In his 1987 address to the OAU, Thomas Sankara warned that “He who feeds you, controls you,” and elsewhere cautioned that, “It is natural to fear to be outside the norm, but the courage to refuse conformity is the beginning of freedom.” In your view, what concrete forms of economic or diplomatic refusal allow African countries to assert autonomy, sovereignty, and justice in today’s international world order, with nested global racial hierarchies, and capitalist expansion?

Everywhere, the struggle to preserve equality or to increase inequality continues. The balance of power is political and, depending on the worldview and the period, gives rise to increasingly sophisticated superstructures to resolve issues of wealth, power, and meaning. The resulting institutions can be immutable for a long time, or they can be brutally overturned, creating new relationships of power and knowledge.

It is up to us, in this exceptional historic moment of redeployment of imperialism in the 21st century, to help complete the efforts of so many people, like Sankara, who have fought for our freedoms and our development. In the current state of disarray and expectation, and without nostalgia, a lucid response from the organic forces of the Great South is inexorably becoming aware of its anti-systemic potential. This presupposes recovering the state’s room for manoeuvre, rediscovering the organizing potential of peoples and the coherence of the convergence of transversal struggles beyond sovereignty against transnationals, war, and the rapacity of the market, and in defense of the equal status of women and the protection of the common good and the environment. This is not a time for nostalgia and mere commemoration, but for understanding that the non-aligned must now have the courage to align themselves against imperialism and reinvent a transinternationalism of peoples. If the latter accepts the leadership of BRICS, the industrial champions of the Great South, it rejects their sub-imperialist temptations and reaches out to the peoples of the core countries to fight barbarism.

I propose transinternationalism starting from the Great South first, so that once it has crystallised, and without sub-imperialism, it can irradiate the peoples of the North whose interests are not so opposed to ours, confronted as they are with the rigours of their uniformising economic, cultural, educational, and political standards and systems. Universality will only exist when other homeomorphic and endogenous equivalents have irrigated it, and when hegemony fades through fertile and reciprocal acculturation.

The Great South must take back the epistemic initiative and restore the sense to participate in the uninhibited construction and non-Eurocentric reconstitution of knowledge. All the peoples and nations that have suffered colonization and continue to suffer its after-effects must learn to work together to emerge from their condition. Whether through South-South cooperation at all levels, bilateral, multilateral, or simply as citizens.

We need to deconstruct the Eurocentrism embedded in our cognitive frames that are deeply enmeshed in our thoughts and practices of knowledges. By transnational, I mean the extra-state and national dimension, both infra- and supra-national, which incorporates progressive internationalisms, mainly those of workers and the jobless, ecologists and feminists. So we’re going beyond the first internationalism and adapting it to the 21st century, to its equivalents in different parts of the world, in order to achieve real universalism. Transinternationalism makes it possible to incorporate internationalism, which itself went beyond the national question by advocating workers’ solidarity, transcending it to deploy politically, socio-culturally, and psychologically a progressive rearguard and vanguard front of organic forces to meet the challenges of the 21st century and beyond.

We need to build a collective internationalist network of resistance to imperialism, starting by strengthening its axis in the most promising parts of its periphery. There is an urgent need for a political level, which exists only sporadically on an event-driven basis. This organized and diverse nebula must bring together, based on Bandung 2 internationalism, the fronts, parties, movements, and individuals likely to propose to the peoples, the alter-globalist network, as well as to the social formations and productive or unemployed forces of the world, an alternative project to capitalism. A project against the modernization of pauperization and technocratic depoliticization, a free, egalitarian, democratic, feminist, and solidarity-based project for the construction of a responsible universalist order without oppression for humans and nature alike. This must be done in a respectful, democratic, and united way, in the diversity of our obedience(s), with the prospect of rebuilding a world labor front conscious of the issue of the commons, the last non-commodified public spaces, and the importance of adopting a universal declaration for the common good of humanity.

The challenge of an anti-systemic response based on the spirit of Bandung should consider the feminist, ecological, and progressive challenge at the heart of any analysis aimed at democratically re-politicizing peoples with a view to an upsurge in the defense of peace, of the commons and an alternative to capitalism. The democratic re-politicization of our popular masses on the basis of dynamic balance and a stand against the militarization of the world requires the re-foundation of a tricontinental front to counter the military impetus of collective imperialism and move toward the equivalent of a 5th International. At the very least, it is important to recall the eight principles we set out in 2006, during the World Social Forum in the Bamako Appeal.

Thank you so much for your time.