Who gets to tell the history of Mau Mau?

David Elstein’s attack on David Olusoga’s docuseries on the legacy of the British empire reveals less about historical error than about the enduring impulse to rehabilitate British colonial rule.

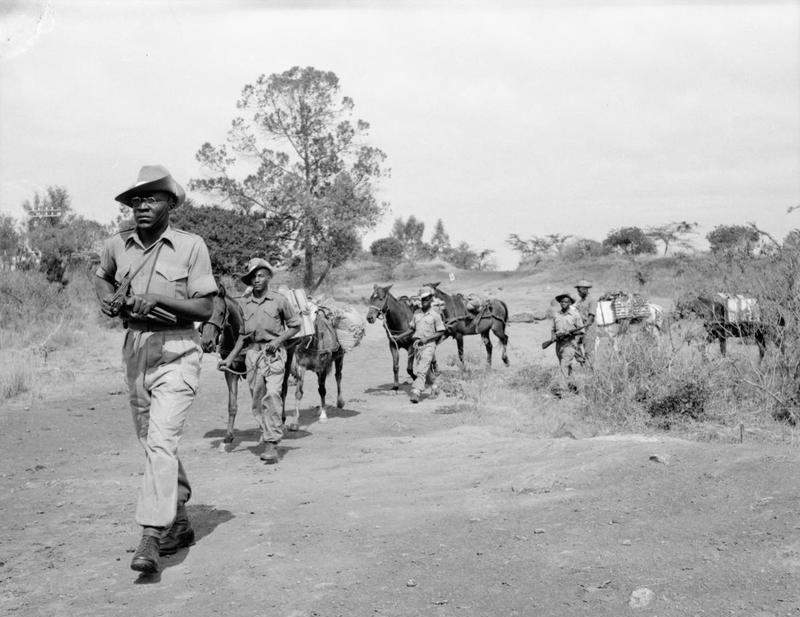

Troops of the King’s African Rifles carrying supplies during operations against the Mau Mau uprising in colonial Kenya, 1952. Public domain image via the UK Ministry of Defence/Imperial War Museums on Wikimedia Commons CC0.

David Elstein’s recent review of David Olusoga’s Empire purports to expose a documentary riddled with historical errors. What it actually reveals is something far more familiar: a deeply apologetic framing of British colonial rule, a selective reading of the Mau Mau Emergency, and an insistence that archival records produced by the colonial state constitute the only legitimate historical truth. The review is not simply flawed, it is structurally incapable of reckoning with the violence of the British Empire.

Elstein opens with mockery, finding Olusoga’s Mau Mau section “unintentionally hilarious.” His first example is not a substantive critique but a pedantic complaint about Dr Riley Linebaugh wearing gloves in the archive. In reality, this is just as likely a stylistic choice. History documentaries have long used gloves and protective gear as a visual shorthand for the historian at work, a familiar trope to signal the handling of “old” or sensitive material. However, anyone who has worked with FCO141 files (which many of the “Operation Legacy” records belong to) knows that gloves are sometimes required, not to protect documents but to protect researchers from pesticides supposedly used on returned colonial materials. Elstein’s astonishment at having used his “bare hands” sets the tone: trivial performative outrage standing in for argument.

From there, he characteristically frames complexity as “error.” His assertion that “no settlers had been killed” by the declaration of Emergency in October 1952 is simply incorrect. Mrs Marie Chapman was killed in September 1952, and Mrs Margaret Wright on October 3, 1952. His broader claim that Mau Mau were “indifferent” to settlers is even more misleading. A glance at the extensive corpus of crime-scene photography is enough to dispel that notion entirely; the visual record makes clear that settlers were neither peripheral nor ignored in Mau Mau strategies of violence. What Elstein presents as correction to the documentary’s claims is instead a familiar rhetorical move: minimizing settler casualties early in the Emergency in order to paint Mau Mau violence as primarily intra-Kikuyu and therefore not a response to the pressures of colonial land policy and structural political exclusion.

Throughout the piece, Elstein consistently re-centers African violence while marginalizing British colonial violence. He rightly notes the inter-African dimensions of the conflict, pointing to its “civil war” aspects, but then treats Mau Mau violence as the central explanatory force. In doing so, he implicitly sidelines the systemic violence of the colonial state—from direct military operations to the widespread use of torture in screening and detention camps, and the coercive practices inflicted on women and children in the “new villages.” He accuses the documentary of lacking “context,” yet his own contextual framing erases the systemic conditions that scholars have demonstrated as fundamental to understanding the conflict.

His treatment of killings at Hola Camp is exemplary. While he does admit the events, his narrative works hard to shift responsibility away from the colonial administration, much like the government did in 1959. The beating to death of 11 detainees becomes, in his phrasing, the tragic result of “poor supervision” and the misguided actions of African guards—a textbook move to obscure the structural violence that authorized the use of force against detainees in the first place. The key fact Elstein ignores is this: Hola did not happen because of rogue guards. It happened because the colonial government formally authorized the use of coercive labour schemes that predictably led to lethal violence. To speak of “lack of nuance,” as he accuses Olusoga of doing, while offering such a decontextualized account is irony bordering on satire.

Equally telling is his dismissal of testimonies from Kenyans. When a descendant of a Hola victim describes burial practices, Elstein labels it a “series of lies.” His immediate presumption that oral testimony—one of the most important and respected forms of historical evidence for Kenyan communities—is “propaganda” reveals far more about his epistemological commitments than about the history itself. The implication is clear: only the colonial archive is a valid source. This is colonial knowledge-making reproduced in 2025.

On detention and villagization, he again accuses Olusoga of exaggeration by citing maximum simultaneous detention figures. But this entirely misses the point. The Emergency was not only about formal detention camps. The villagization program—the forced relocation of more than a million Kikuyu, Embu, and Meru civilians into fortified villages—constituted a vast carceral system in its own right, one that scholars universally understand as a central component of colonial control. To treat detention as limited to camp populations is reductive to the point of distortion.

Most fundamentally, Elstein’s review operates through suggestion rather than argument. He repeatedly claims that Olusoga “suppresses truth” or “distorts,” yet the examples he provides are themselves partial, selective, or simply inaccurate. This is not accidental. His piece reproduces a narrative long used to defend British imperial conduct: that Mau Mau violence was endemic and fundamentally intra-African—while British violence was bureaucratic, legal, regrettable perhaps, but fundamentally excusable. Elstein’s review is less a work of historical scrutiny than a contribution to an ongoing political project to rehabilitate empire.

What is most disturbing is the review’s final turn: the claim that Olusoga “airbrushes” African victims of Mau Mau by focusing on colonial violence. This is a false dichotomy. It is entirely possible—and historically necessary—to acknowledge violence committed by Mau Mau fighters while also analyzing the overwhelming structural violence, coercion, and racialized governance of the colonial state. Only someone intent on preserving British innocence would fail to understand that both histories can, and must, be told together.

Elstein’s review does not correct the record. It replays a very old one. It is less a critique of a documentary than an attempt to reassert colonial narratives at a moment when public representations of the British Empire have finally,in some spaces, become more nuanced, honest, inclusive, and more critical. In that sense, the review is not unintentionally hilarious. It is entirely predictable.