To revolutionize a culture

The writer on Frank’s Archive, based on her father's records, that explores the different functions of books, power and knowledge.

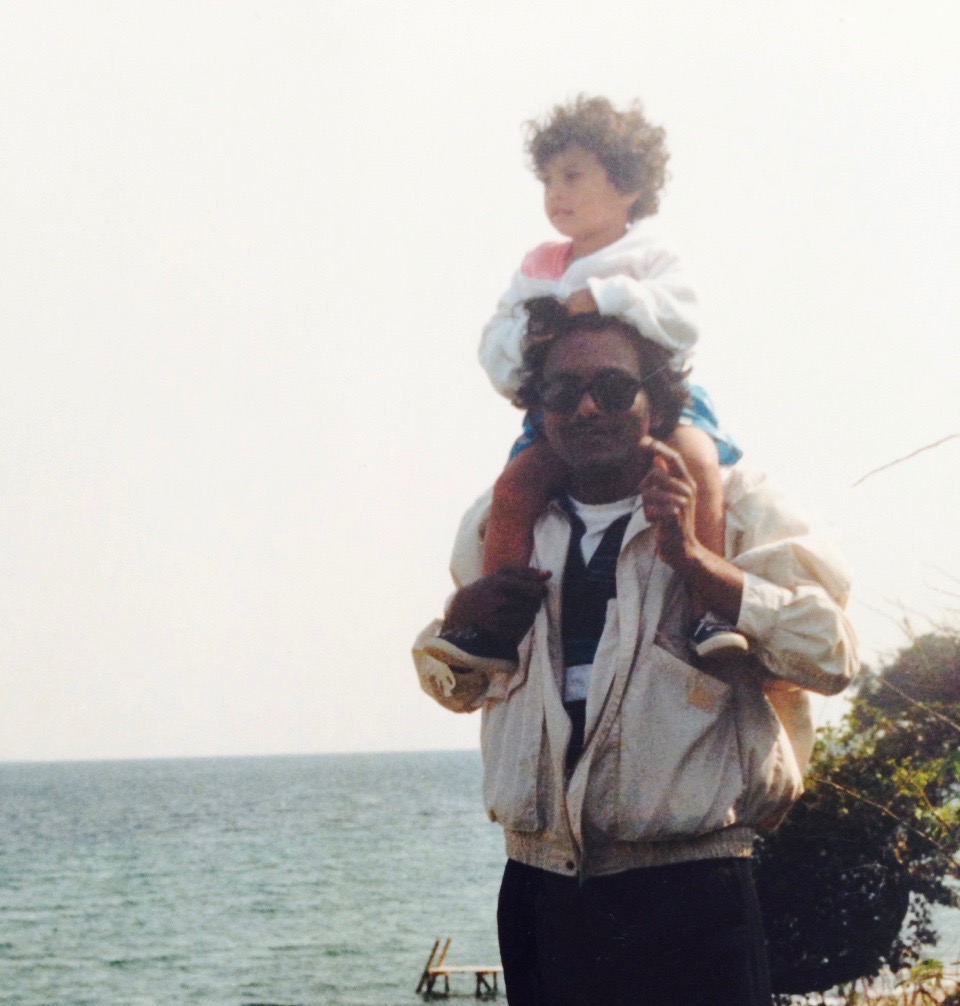

Chandra Frank, as a child, with her father, J.E. Frank, in Portugal. (From Frank's Archive Tumblr.)

My father, J.E. Frank, has left me numerous books relating to race, class, apartheid and politics in South Africa and the United Kingdom. Leaving South Africa in the early 70s, my father decided to sail around the world and eventually jumped ship in London where he became active in the anti-apartheid struggle and worked with the Institute of Race Relations. At a young age I realized politics must be something important–as at one occasion my beloved Spice Girls poster was replaced by an African National Congress flag without any warning. Something to do with capitalism and the commercial music industry–just big words for me at the time.

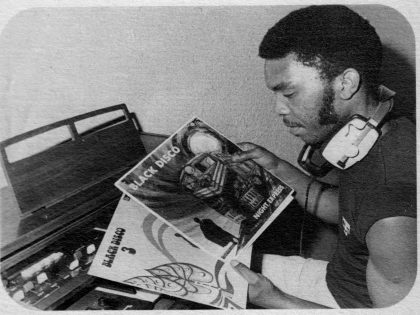

Politically active thinkers tend to have a lot of books–and listen to a lot of jazz–so after I inherited his collection I became interested in the multiple functions of the books. The collection inspired both my father and me during our studies, lives and involvement in anti-racist work. The idea of transgenerational memory and heritage is key to exploring the different meanings of the books. A lot of the ideas and theory developed by writers such as Sivanandan, Fanon, Biko, Cabral and Jackson are still relevant and useful for my generation today. The books but also music such as records by Louis Moholo Moholo and Chris McGregor inform our ideas on resistance and hopefully offer new understandings on the act of archiving resistance.

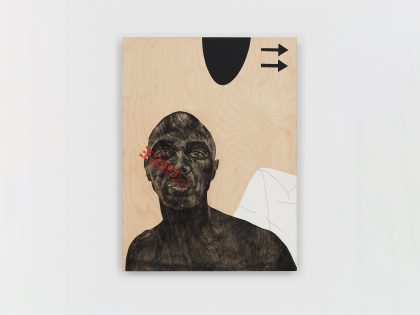

Frank’s Archive, name for my father, is a project that explores the different functions of books, power and knowledge. You can visit the archive here. Frank’s Archive is an on-going project that doesn’t necessarily have a beginning or an end.

Below is an excerpt from Ambalavaner Sivanandan that is part of the archive. Sivanandan is a writer and former director of the Institute of Race Relations in London. He is seen as one of the leading black intellectual thinkers in the UK. A Different Hunger: Writings on Black Resistance (1982) is a compilation of non-fiction articles.

But to revolutionize a culture, one first needs to make a radical assessment of it. That assessment, that revolutionary perspective, by virtue of his historical situation is provided by the black man. For it is with the cultural manifestations of racism in his daily life that he must contend. Racial prejudice and discrimination, he recognizes, are not a matter of individual attitudes, but the sickness of a whole society carried in its culture. And his survival as a black man in white society requires that the constantly questions and challenges every aspect of white life even as he meets it. White speech, white schooling, white law, white work, white religion, white love, even white lies – they are all measured on the touchstone of his experience. He discovers, for instance, that white schools make for white superiority, that white law equals one law for the white and and another for the black, that white work relegates him to the worst jobs irrespective of skill, that even white Jesus and white Marx who are supposed to save him are not really not in the same street, so to speak, as black Gandhi and black Cabral.

In his everyday life he fights the particulars of white cultural superiority, in his conceptual life he fights the ideology of white cultural hegemony. In the process he engenders not perhaps a revolutionary culture, but certainly a revolutionary practice within that culture.

From A. Sivanandan, (1982: 95) .