Israel and the asylum seekers

If Israel doesn't send asylum seekers back to the countries they fled from, it deports them to "third countries."

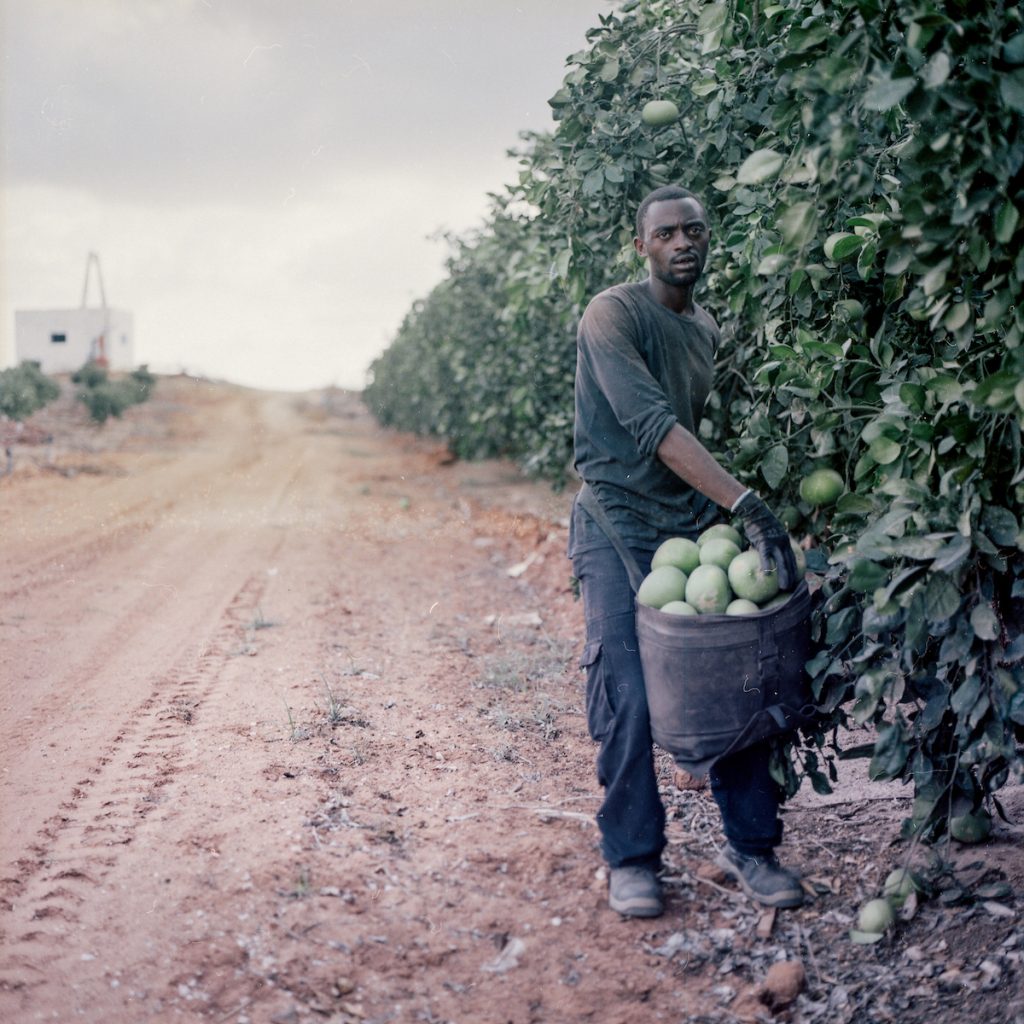

A Sudanese migrant worker in Israel (Photo: Amira_A via Flickr CC).

When Israeli activist Dafna Lichtamn got home from Mozambique two months ago, she had a layover in Addis Ababa airport. Walking around the main Ethiopian airport she suddenly ran into an old friend, Sadik Alsadik, an asylum seeker from Darfur who had spent the past five years in Israel. When Lichtman met him it was his sixth day wondering around the airport. A few days earlier Alsadik was facing a very difficult decision: he was given the choice to either go to Holot, the new “open” detention facility in the Israeli desert, or to an unnamed “African country”–one of those Israel refers to as “third countries” (meaning not the country of origin nor Israel). Even though never officially confirmed, these “third countries” are well known amongst asylum seekers as referring to Uganda and Rwanda, countries with which Israel keeps cozy relationships. Knowing just how open Holot is really is, Alsadik chose the second option, thinking that means freedom.

When Alsadik found himself on a plane to Ethiopia he assumed that to be the third country. But when he tried to leave the airport he was told by Ethiopian officials that he was scheduled to fly on the next flight to Sudan, the same country he escaped from. Alsadik refused to board the flight that he was told was booked for him in Israel. His luggage in fact, they told him, is already in Khartoum.

For Alsadik going back to Sudan means a death sentence. The danger for him in Sudan is double: not only as a Darfurian but also as someone who came from Israel and can be suspected as an Israeli collaborator. He wanted to leave the airport but wasn’t allowed to, since he didn’t the required documents to enter the country.

Lichtman posted the story on Facebook and Israeli media picked it up. After two more days in Addis Ababa Alsadik was forced to go back to Israel: straight to detention.

Since then, human rights organizations in Israel have been trying to assist Alsadik to find a new solution that wouldn’t include him being imprisoned. What made the procedures even more complicated was the fact that since being taken to the airport Alsadik was given a different identity. According to Alsadik, whose own passport was taken from him when he first arrived in Israel, Israeli immigration authority gave him a passport of someone named Ahmed Ibrahim, with which he left Israel. When different activists and journalists, including Galei Zahal radio station, tried to reach Alsadik, while he’s being transferred and detained, they have been told by the immigration authority that there is no such name on its records. They were, however, able to find Alsadik under the name Ahmed Ibrahim.

A month later, another Israeli activist, named Rami Gudovitch, landed in Addis Ababa airport on his way to Uganda. There he met nine Eritreans asylum seekers that had just arrived from Israel. They, too, were told in Addis (against what they knew when they left Israel) that they need to fly to Khartoum. They refused, fearing that from Khartoum they would be deported back to Asmara. They were also accused that they are carrying fake documents. The head of the immigration department at the airport was determined to arrest them. As far as we know, they are still detained in Ethiopia.

As for Alsadik, while spending the last two months in Holot, his lawyers petitioned for his release, basing their argument on the fact Israel is the one that brought him in this time — therefore he is no longer an “infiltrator” under the infiltration law definition.

Alsadik’s hearing took place a week ago in the newly founded appeals tribunal for immigration issues, originally named “the foreigners’ court”. The verdict that was given on Thursday determined that Alsadik is still an infiltrator and he will stay in Holot indefinitely.

Immigration activists who were present in the hearing on Monday report that in response to Alsadik’s lawyer persistence to get an answer to the fake passport question the judge said: “We live in a world of fluid identities.”