What Binyavanga thinks of the Caine Prize

The inaugural winner of the Caine Prize for short fiction opines on the useless rivalry between Kenyans and Nigerians about who has won more Caine Prizes.

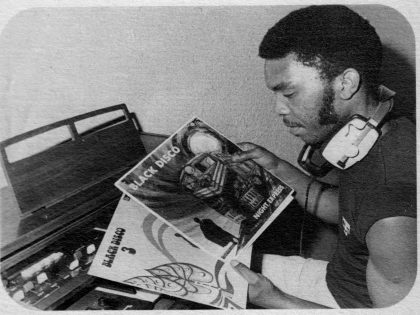

Image credit Erik (HASH) Hersman via Flickr (CC).

The website, This is Africa, is prone to tabloid headlines (they’ve been running a ton of posts about sex lately), but Nigerian journalist Chiagozie Nwonwu‘s interview with Binyavanga Wainaina (writer, commentator, rights defender and “a public figure, not D’Banj, but with enough people”) is worth all the sensationalism.

In the interview, Binyavanga covers a lot of ground: Nigerians moving to Nairobi, the reaction in both Nigeria and Kenya to his coming out last year (“my gay drama”), that he has “three per cent Nigerianness in my body,” the impact of cultural phenomena like Chocolate City, P-Square, Victoria Kimani, Wazobia, and, most explosively, the Caine Prize for African Short Story Writing.

We tweeted from the piece earlier today, but felt it would be better to just embed Binyavanga’s answer to a question about Kenyan and Nigerian rivalries about who has won more Caine Prizes:

I am going to take this first to another road because I think all you Nigerian literati are way too addicted to the Caine Prize. I give the Caine Prize its due credit, but it just isn’t our institution. All these young people who are ending up in that place were built up by many people’s work. If there was no Saraba, if there was no Farafina workshop, if there was no Cassava Republic, if there was no Tolu Ogunlesi meeting Nick in South Africa and then workshoping stories, if there was no Ivor Hartmann, if there were no thirty thousand Facebook groups that I know off or don’t know, there will be no Okwiri, there will be no Elnathan, etc. What is happening is you people are allowing the Caine Prize to receive funding and build itself as a brand and make money and people’s career there in London while the vast majority of these institutions are vastly underfunded and vastly ungrown, and they are the ones who create the ground that is building these new writers. Why do I have to sit in interviews with Nigerian journalists who want to help Caine Prize get more money in the sixth richest country in the world?

I want people to say, Okwiri, who won the Caine Prize, is the founder of Jalada, an online magazine that has won five prizes in the last year and published, I think, the most exciting fiction I’ve seen in ten years. Just that magazine, has more excitement than many known ones, but they are invisible. Seven years ago, I came here (Nigeria) and I felt nothing is going on in the online community in Kenya. Then Dami Ajayi and Emmanuel Iduma went and started Saraba. People there in Kenya smelled Saraba, made their own and that was it. Now, writers in America and approaching writers published in Saraba and these online magazines to give them fellowships abroad. Okwiri made her name long before the Caine prize. I picked her for a long list of under-20 writers. I didn’t even know her then. Because the ecosystem is so big that you don’t even know each other anymore. Up until now, I’ve not met her and if I have, we bumped into each other. I know she wrote a review of my book launch, but I don’t remember meeting her. The idea that she won the Caine Prize and journalists now want to feed the fact that she was made by the Caine Prize is unmaking her. You ask any smart Kenyan writer who is in the game, they tell you Okwiri is the new be. And we are talking two years ago. We must lose this shit. Give due credit but don’t go giving free money and free legitimacy. Because the Caine Prize right now needs your legitimacy to get money. They take press clipping from all Nigerian media and use that to source for funding. We need to focus on how we can grow our own ecosystem.